In conversation with Cedar Lewisohn

“I want art to save people’s lives, like it saved mine.”

- Cedar Lewisohn

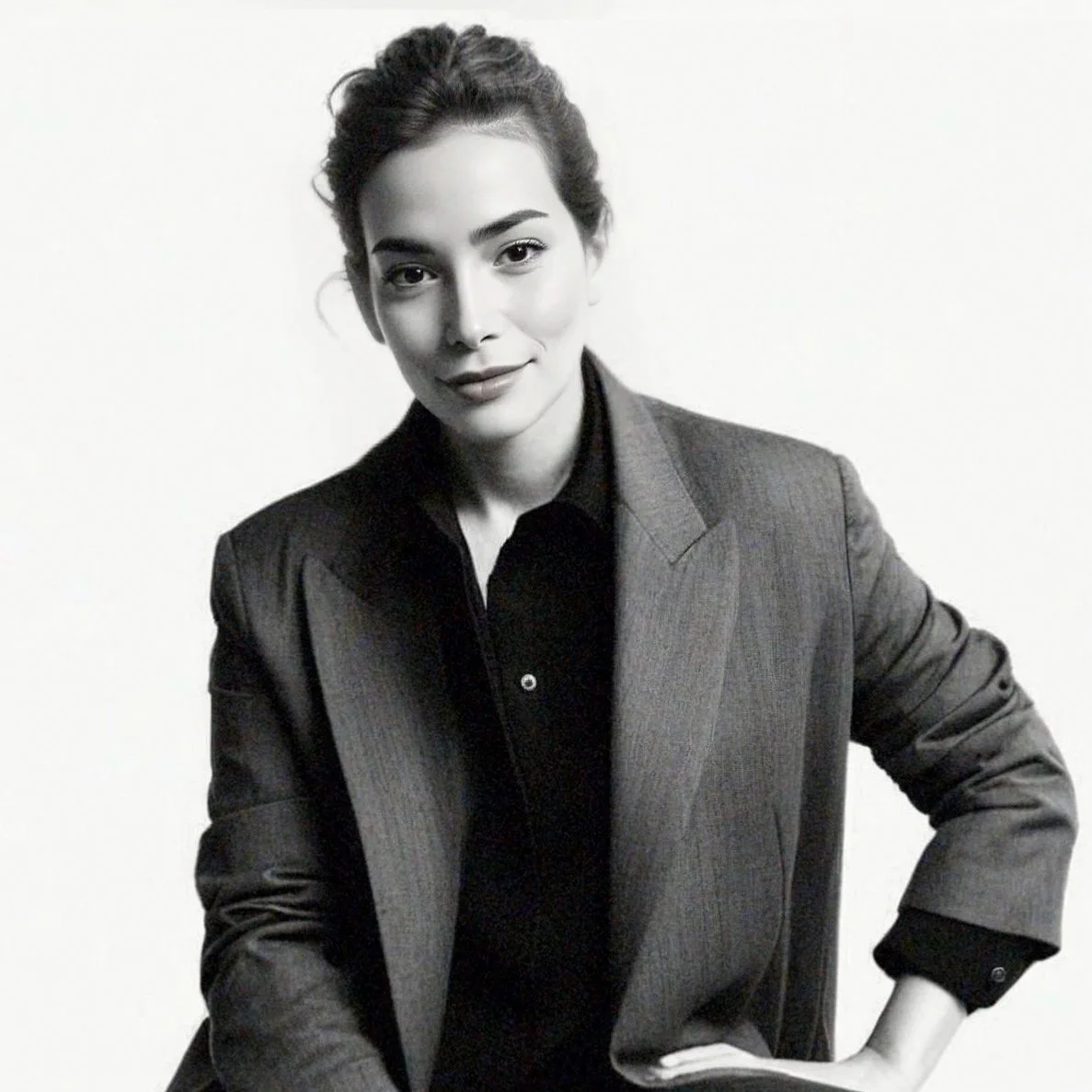

Cedar Lewisohn Photography by Sophie Dawson.

Cedar Lewisohn is a versatile artist, writer, and curator recognised for his contributions to esteemed institutions such as Tate Britain, Tate Modern, and The British Council. He boasts three published books—Street Art (Tate, 2008), Abstract Graffiti (Marrell, 2011), and The Marduk Prophecy (Slimvolume, 2020)—as well as a collection of edited and self-published works. Notably, he curated the groundbreaking Street Art exhibition at Tate Modern and played a pivotal role in The Museum of London’s Dub London project. In 2020, he assumed the position of Site Design curator for The Southbank Centre.

Can you tell us about your background in the arts, and how you ended up working as a curator?

I studied sculpture, what seems like a thousand years ago. I was always in to organising quirky little projects.. but I just used to do this, kind of for fun. Then my big X-Factor moment came when I got a curatorial training placement at Tate Modern. I went from working in an extremely rough pool bar on the South side of Glasgow, to the curatorial offices at Tate Modern. I still pour a mean Voddy and Iron Bru though.

According to you, what does it mean to be a curator today?

The word “curator” has changed meaning quite significantly over the last few years. I’m a little bit of a traditionalist when it comes to this subject. But I also don’t feel strongly about it. So I actually prefer there term “Exhibition Maker” for what I do. It’s a bit more precise, in today’s context. I think Tesco Supermarket have a Curator of Cheeses.

How would you define your curatorial process?

I work for institutions—so its very meeting based with lots of sign- off processes. I try to do the best I can for the artists I work with. I’m their champion. I also want to represent audiences. I want audiences to fall in love with the art we show. I programme a lot of work in outside and public spaces, so we have to think slightly differently about how the audience engage with the work.

Have any artists, writers, curators, and other creative thinkers inspired your curatorial practice?

Many artists and creative thinkers inspire me. Too many to list. But I also like to think outside the box. I’m not really into Football, for example, but I love to look at the leadership styles of Football managers. Sir Alex Fegason, Brian Cluff, Arsène Wenger, they inspire me. In some ways, making exhibitions and art projects is like football. You need to get the ball, down the field, and in the net. If you are really good, you do it with a little bit of style.

You recently curated Winter Light 2023/24 at the Southbank Centre. Can you tell us a bit about how the exhibition came together?

Winter Light first came about in the first lock down. It’s a way of animating our spaces with light during the winter months. We do new commissions and also show works we have displayed before. There are some fantastic works on site at the Southbank Centre this year; a beautiful new poetic text by Tim Etchells, a great project where school children from Lambeth have worked with the architecture firm Squire and Partners to make light works that are in the windows of The Queen Elizabeth Hall, an amazing, huge glittering sculptural stage by Italian artist Marinella Sanatore, and a massive neon spinning sphere by one of the early pioneers of Light Art, Fred Tschida. All this you can see for free, walking around the Southbank Centre until early January.

Fred Tschida, Sphere, 2000. Photo by Owen Billcliffe.

What is the most challenging thing about what you do?

We actually have great teams of people at the Southbank Centre who help make our projects happen. From the Health and Safety team, the Production teams who install the works, to the people who sort the Post out. We all make it happen. So instead of thinking about challenges, I want to thank all the teams at the Southbank Centre that make the Winter Light project happen.

What kind of experience do you want visitors to have from the Winter Light exhibition?

I’ll tell you a quick story. When I was about 17 years old, I came to an exhibition at the Hayward Gallery by the artist Yves Klein. Klein had lots of mad ideas about public sculpture, like sculptures made of fire, sculpture made of pure gold in public, that sort of thing. Lots of his ideas could not be done because they were too wild. I now work for the Hayward Gallery and I’m all about realising Yves Klein’s visions. The more out of this world the idea, the more public love it. I want art to save people’s lives, like it saved mine.

What are some memorable things has happened throughout your career?

I’m dyslexic and I’ve written about three books so far. I did a project which covered Tate Modern in graffiti. During the first Covid lockdown - while most institutions were closing - along with my boss, Ralph Rugoff, we commissioned a series of large-scale artworks which were displayed around our site, responding to the situation. I think we were the first arts organisation in Europe to do a physical project in response to Covid. But, honestly, I haven’t really started to do the projects I want to do yet.

What is the best advice you have ever received?

Years ago, I met Quentin Crisp in New York. He said – “Make being yourself your job”.

We like to discover new artists in our interviews. Can you recommend three artists that you think our readers should watch out for or discover this year?

Well, there are many artists in Winter Light to look into. Leo Villareal has his amazing work Cosmic Bloom, projected on to the Royal Festival Hall. The work has a soundtrack by Kode 9, which can be accessed by QR code. The artists Denman and Gould worked with Garden Designer Maeve Polkinhorn this summer to make a piece called Haven, on our site. We loved it so much that we have left it installed over winter. It’s basically a pocket meadow with indigenous UK based plants and flowers. It doubles as a hotel for insects. Lastly, David Ogle’s work Loomin along Queens Walk is really worth checking out. He’s turned our trees into a kind of cyber punk neon selfie zone.

Do you have any tips for a young person aspiring to work within the art industry?

The thing you love, that the art industry ignores, may be just the thing that art industry needs.

Who is Cedar Lewisohn outside the ‘office’?

I’m happily settling into by status as a middle aged man. I’m a kind of typical introverted Gen X’er. I feel outrage at everything that’s happening, but I also appreciate a really good, Eccles cake from St. John’s bakery.

Winter Light 2023/24 will be on display throughout the Southbank Centre until 7 January 2024.

Website: cedarlewisohn.com

Instagram: @cedarlewisohn