Beeple and Blockchain: The rise in cryptoart

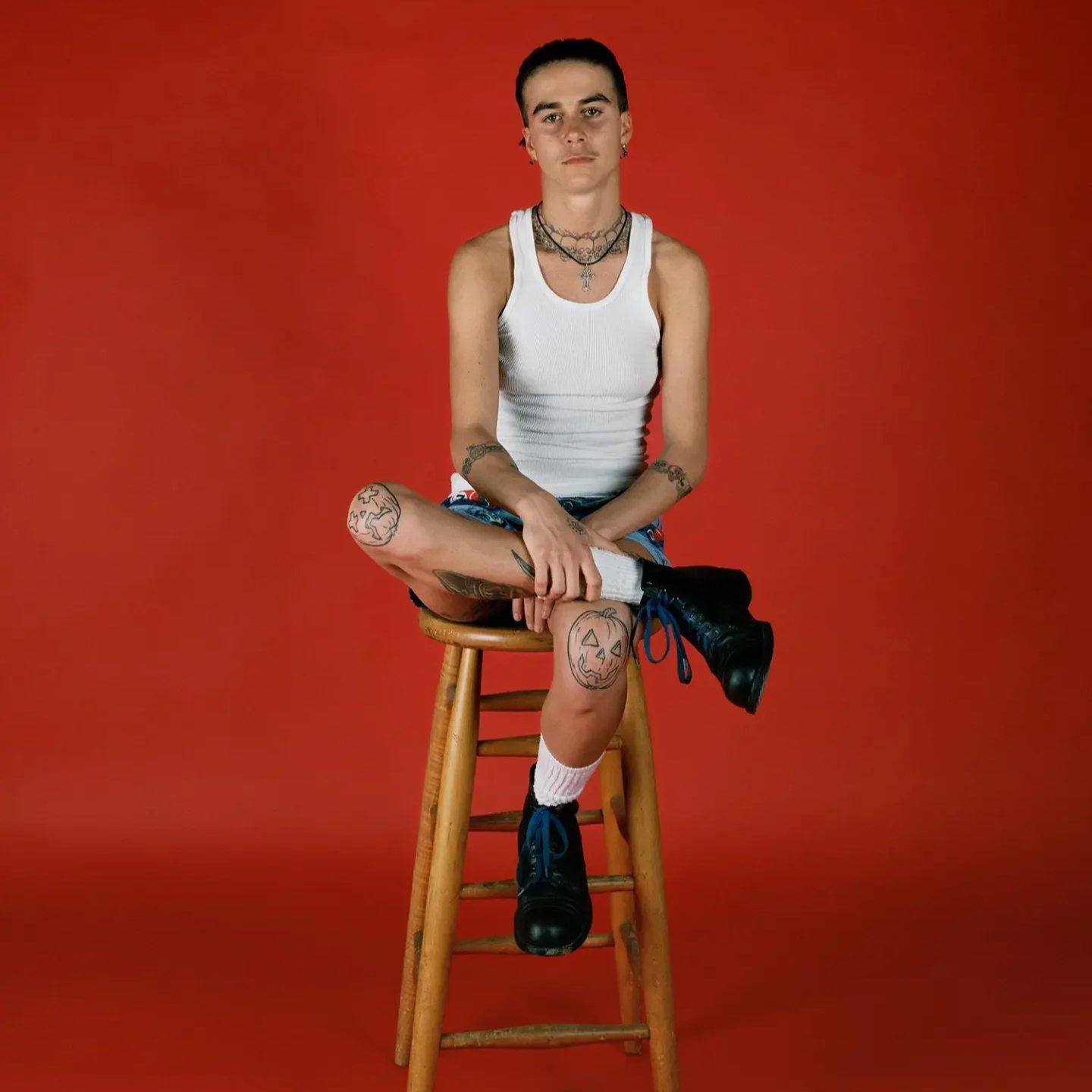

The sale of ‘Everydays: The First 5,000 Days’, a piece of cryptoart created by digital artist Beeple (otherwise known as Mike Winkelmann), created history in the art world earlier this year. Selling for $69 million, ‘Everydays’ became the first piece of cryptoart to be sold by Christie’s auction house and made Beeple the third most expensive living artist at auction. But the high sale price is not the only thing that has allowed this story to gain widespread interest. The art world, one that has long been inaccessible to those without wealth and status, has suddenly become a place that almost anyone can indulge in, with the rise of cryptoart giving artists the opportunity to sell their work without the use of galleries and turning the concept of ownership on its head.

NFTs (non-fungible tokens)

The trade in cryptoart relates to the exchange of NFTs, non-fungible tokens, whose sales have increased during the last few months with prominent cultural figures selling digital assets. Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey recently sold his first ever tweet and contemporary Krista Kim made a landmark sale when her digital landscape piece ‘Mars House’ became the the world’s first NFT house. But when purchases of cryptoart are made, the buyer does not own a piece of art in the same way the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia owns Da Vinci’s ‘Salvator Mundi’ or Leon Black owns Edvard Munch’s ‘The Scream’.

Ultimately, when purchasing a piece of cryptoart, or a non-fungible token, the purchaser becomes the sole owner of a cryptographic asset. Many will be familiar with the cryptocurrency Bitcoin, but may not be so familiar with Ethereum, the second largest cryptocurrency marketplace. The piece of cryptoart being purchased is simply a string of code that is found on the Ethereum blockchain. Tying this to the concept of non-fungibility, when buying cryptoart, the buyer is purchasing the certificate of authenticity, i.e., they become the sole owner of a string of code.

Fungibility is based on the idea of equal value between assets. If you give your friend a £20 note and they return that money to you in the form of twenty £1 coins, it does not matter. They have the exact same value (although admittedly, it is more annoying to be jingling along the street with twenty pound coins in your pocket). However, if something is non-fungible, the same value does not exist between the assets. Imagine now that you lend your friend a top. When the time comes to give it back, your friend hands you a different one. This is non-fungible, it is not acceptable for them to give you a different one back because it does not have the same value.

In terms of cryptoart, when you purchase a non-fungible token, you own the original copy of a cryptographic asset. No matter how many times someone replicates the image, you can always say you have the original version (unless you trade it of course). Think of how many markets sell prints of Gustav Klimt’s ‘The Kiss’ or Jack Vettriano’s ‘The Singing Butler’. Dozens. Whilst these are nice to look at, the originals in the Osterreichische Galerie Belvedere Museum and the Aberdeen Art Gallery are far more valuable.

Implications for the art world

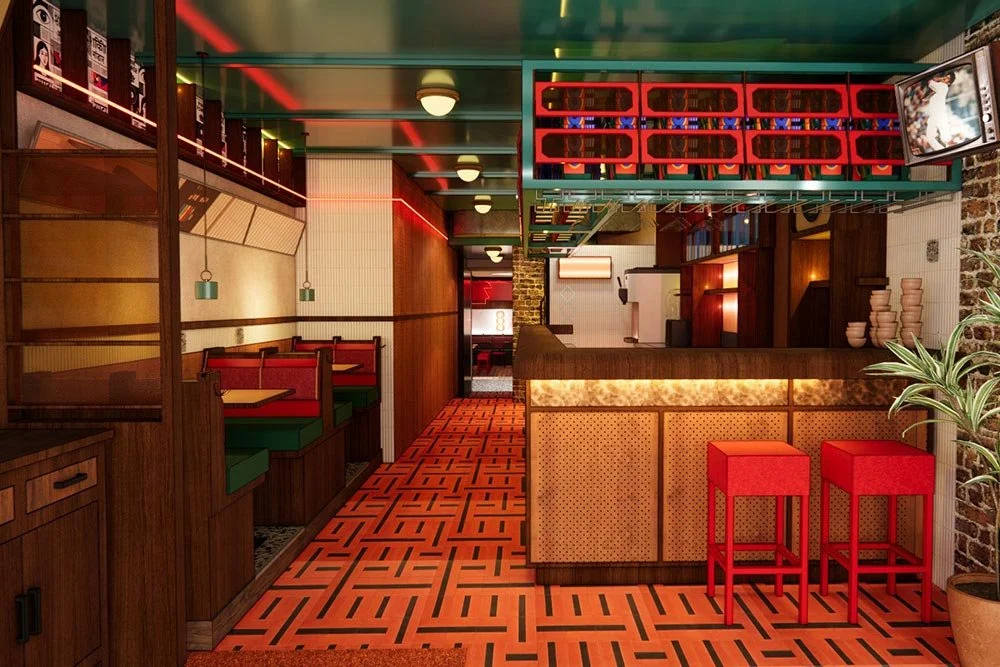

It is easy to see the confusion around why someone might want to purchase an NFT given the buyer does not actually receive a physical item. It is even more confusing when you think about the fact that the image you are buying can be replicated any number of times across the internet. However, many have still embraced cryptoart seeing it as something that may increase in value in the same way physical pieces of art do. Others see this as an opportunity to sell artwork without the assistance of galleries as well as a way to turn a profit every time the NFT changes hands, potentially providing them with a steady income for many years.

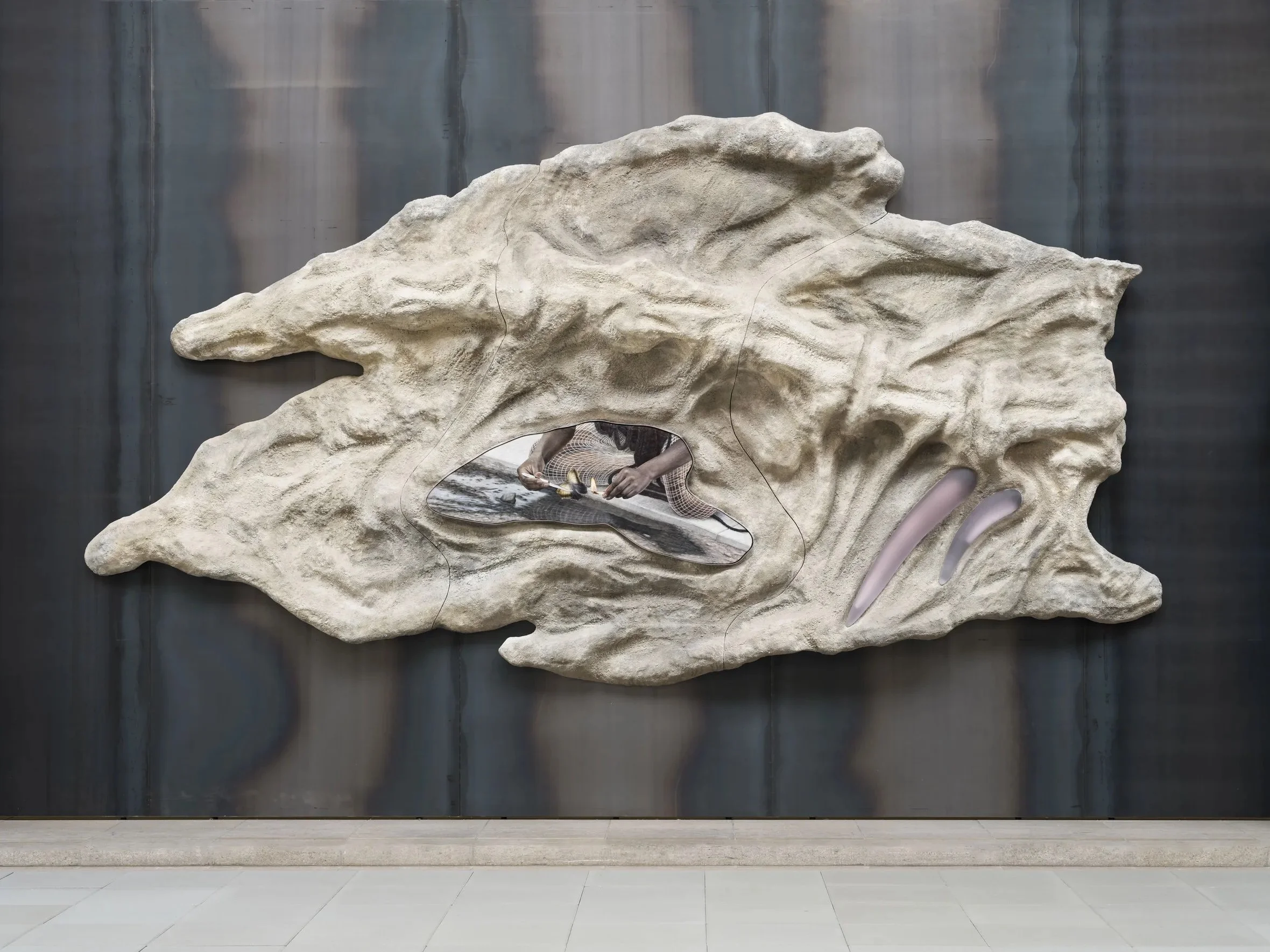

Additionally, cryptoart could mean a new way of viewing art work and a reinterpretation of how we assign value to something. Will we soon be satisfied with viewing Yayoi Kusama’s ‘Infinity Mirror Rooms’ online? Will queues for a quick five-second glimpse of the Mona Lisa be a thing of the past? The pandemic has shown there is an opportunity for much of our daily lives to be managed and experienced online, but the swarms of people returning to pubs, galleries and restaurants as restrictions have begun to ease suggests we still prefer the real thing.

The rise of cryptoart could also have a catastrophic effect on the environment. Every time a transaction occurs on the Ethereum blockchain, a ‘proof of work’ is required. In short, this is an algorithm that is used to confirm a transaction and secure cryptocurrencies. In order for the ‘proof of work’ to take place, expensive and specialised computers are needed to perform calculations which use a huge amount of energy, so much so that after conducting several large proof of work calculations in Bitcoin, Elon Musk had released more carbon emissions into the air in a few days than the amount of carbon saved through all Tesla sales.

Pandemic fad or the future of art?

The sale of ‘Everydays’ has undoubtedly caused a shift in the world of art, making it more accessible for upcoming artists who might have struggled to get their work into galleries. Opportunities for playing with form have also become available, moving away from more traditional art mediums. Unfortunately, it has also raised questions about whether the trade in cryptoassets can continue given the environmental impact they have as well as the issue of regulation surrounding them. What remains to be seen is whether we are ready to shift towards a future where the ownership of assets is purely digital or whether we will continue to prefer the physical thing.

Words by Emma Chadwick