Coronavirus economy - the worst is yet to come

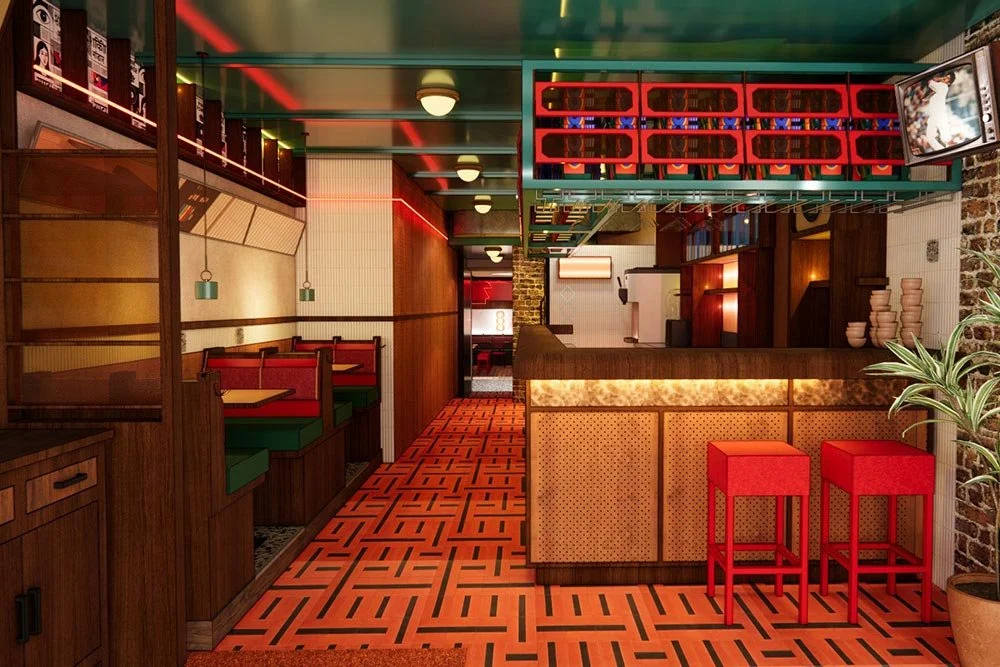

With restaurants, pubs, shops, gyms and workplaces filling up once more, walking through the streets of London now almost makes you forget the economy has taken a serious punch.

The UK economy is in a better situation than some economists thought we would be in today, so much so, that in July, the Bank of England’s chief economist said Britain was enjoying a V-shaped recovery, meaning that it was bouncing back quickly.

Sadly, that picture is now changing for the worse. With the rate of reinfection once again rising, the amount of money the British public is likely to spend in the coming months will likely drop once again. Government support measures that have kept many businesses from going bankrupt and millions of people in work will soon come to an end.

A word on uncertainty: It would be easy to write that the UK economy is about to fall into a depression that makes the 2008 global financial crisis seem more like a daydream than a nightmare; however, there is so much uncertainty in the current environment, that no one knows if that is the case. With so many unprecedented events swirling around the world, it is difficult to be sure of anything. A global pandemic, Brexit, the US currently being led by a racist cheesepuff. These are circumstances crystal ball-gazing economists find difficult to navigate.

Nevertheless, several indicators suggest we should be negative about the rest of 2020’s economic prospects.

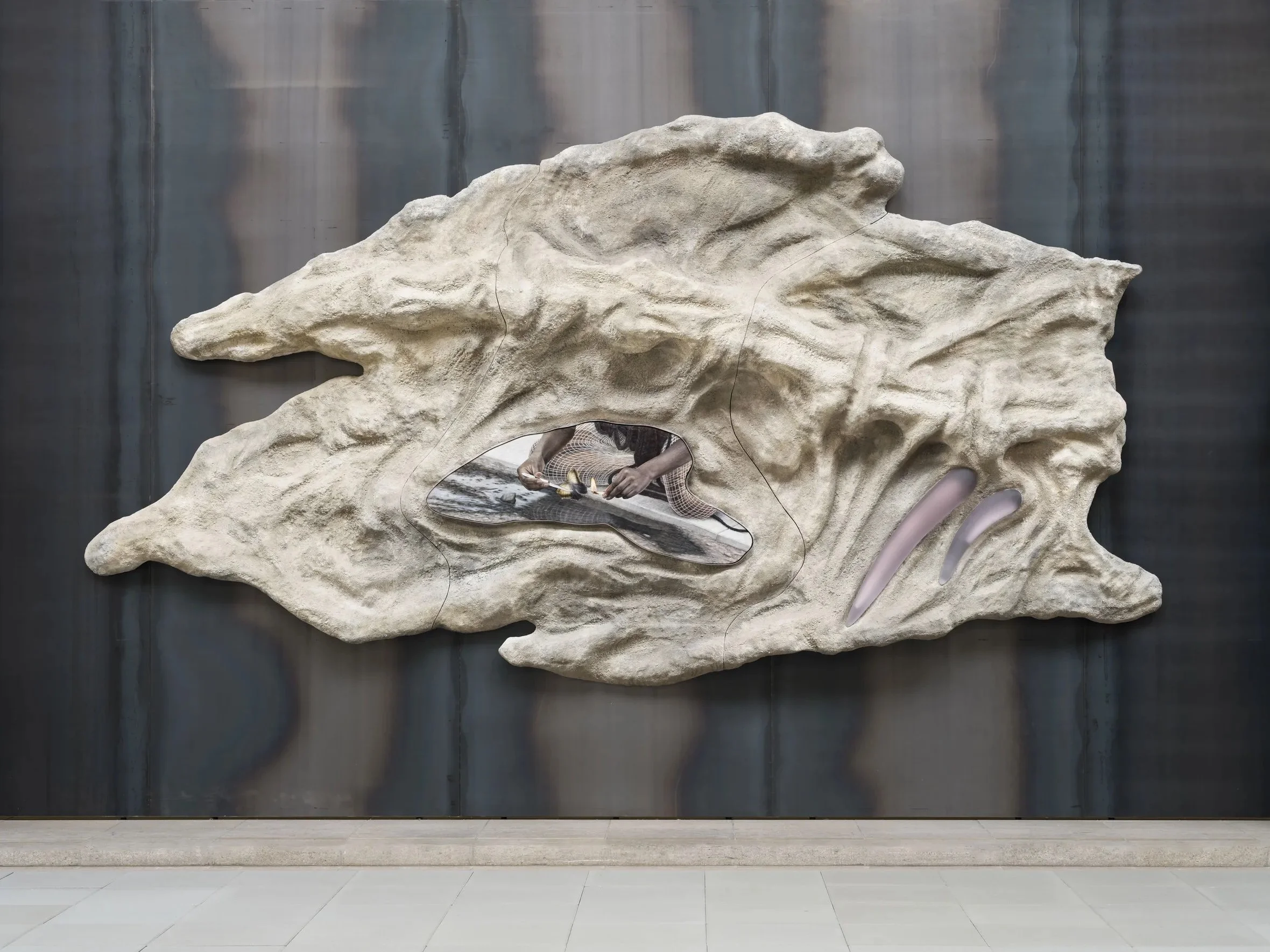

Image: Claus Grunstaudl

As mentioned earlier, the furlough scheme, which saw millions of workers across the nation put on 80% of their salary while they did not work, ends in October. The number of workers on the scheme has already dropped from 30% in May to 11% in mid-August, a significant drop. This has led some to assume the remaining 11% will return to work as normal.

However, sadly, research suggests the remaining 11% likely work for companies that have suffered significantly and will be unable to continue to pay those salaries come October.

Essentially, the UK could experience a catastrophic level of unemployment, which would have a destructive spiral effect on the economy.

Effects of the coronavirus that have increased income inequality in the UK will have a further negative effect on the economy in the coming months. It is more than likely that you have seen this income inequality yourself

Perhaps you have a friend (let’s call her friend A) who got to keep her job throughout the lockdown. She worked from home, continuing to receive her normal salary, as well as save a previously inconceivable amount because she no longer had to travel and could not enjoy any leisure activities at all.

You might have another friend, friend B, who may have lost his job early in the crisis, or who was working on a zero hours contract and thus had no work, or a friend who was not eligible for the furlough scheme on account of a tax code fiasco.

Friend B will have had to pay rent and food, without any income and very little support from the government (some people on universal credit receive less than £100 a month to live off). In a very difficult job market, friend B’s chances of finding a new job are dwindling as his savings run out.

As October comes, we will have a whole new fresh wave of Friend Bs, thus increasing the level of economic inequality in the UK.

These dynamics are actually much worse for the economy in the long-term. While the rich have got richer, research shows that economies with a more even spread of money get going quicker, because when everyone has money, everyone spends more.

This is all assuming we do not have a second wave. In the case of another wave, we are unlikely to benefit from the generosity of the Conservative party once more. We will likely see local lockdowns and restrictions, which could see whole cities locked away, unable to work, without the support of national support systems.

There is no furlough scheme available for a locked down Birmingham alone, for example. Local households and companies would bear the economic costs of local lockdowns to a much greater extent than with the national lockdown we have already experienced.

This almost dystopian scenario does not even factor in Brexit, which could throw another, giant, economy-stalling spanner in the works.

I hate to be the bearer of bad news, but if you think the UK has been through the worst, economically speaking, it currently looks highly likely that you are mistaken.

Words by Katharine Hidalgo