In conversation with Judith Clark

“I love the discipline of exhibiting fashion as much as I did 30 years ago. It never exhausts itself for me …”

- Judith Clark

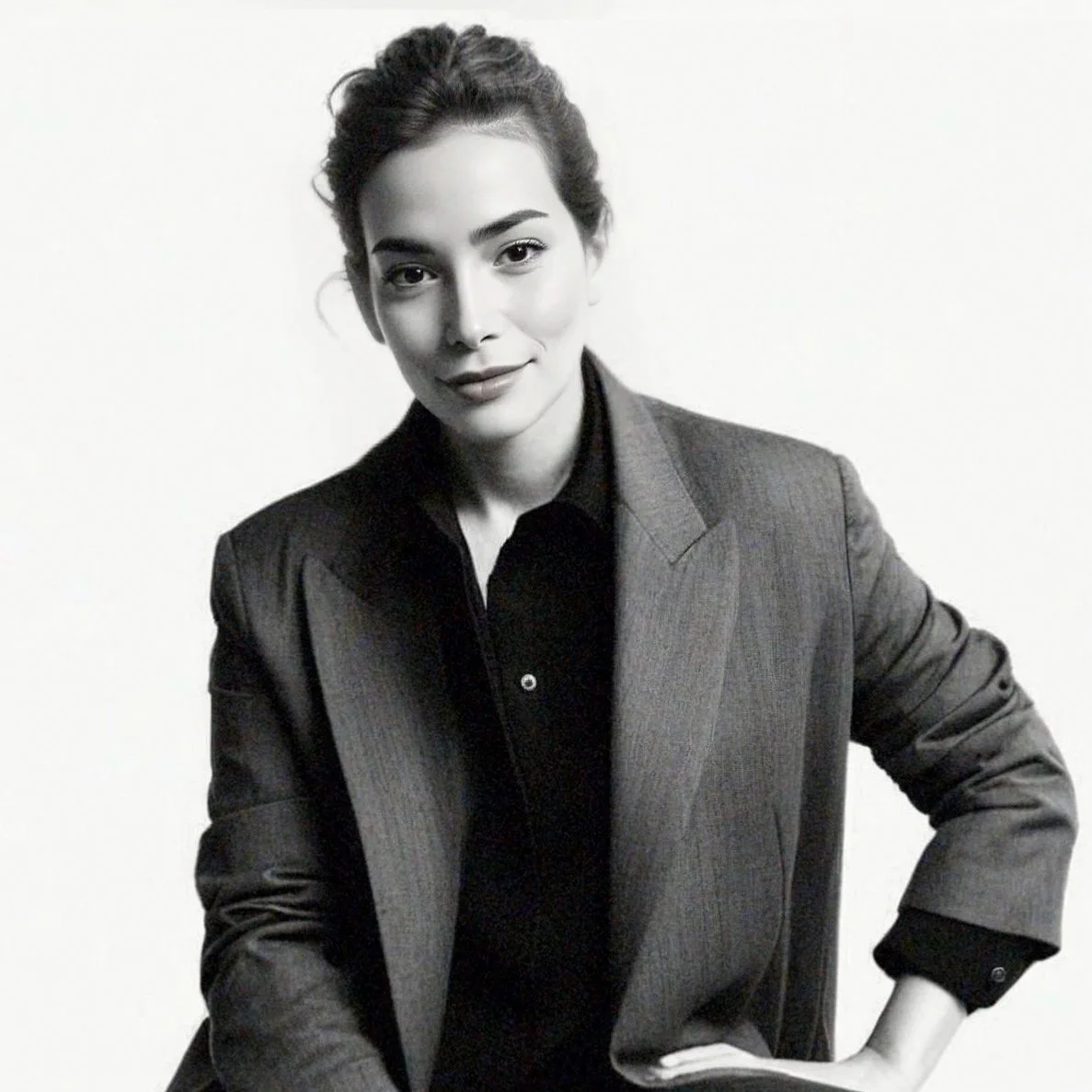

Portrait of Judith Clark, UAL. Photo: Loro Piana.

Judith Clark is a curator and fashion exhibition-maker, and currently Professor of Fashion and Museology at the University of the Arts London. She lectures on the MA Fashion Curation and is a founding Director of the Centre for Fashion Curation. From 1997 to 2002, she ran London’s first experimental fashion gallery in Notting Hill, and in 2020, she launched a new interdisciplinary studio space on Golborne Road, West London. Clark has curated major dress exhibitions internationally across galleries and museums, most recently If You Know You Know: Loro Piana’s Quest for Excellence at the Museum of Art Pudong, Shanghai (March–May 2025).

We recently caught up with Judith to discuss her latest project, I-01: Aprons, a collaborative residency with cultural historian and writer Carol Tulloch, which took place at Chelsea Space, UAL Chelsea College of Arts.

What originally drew you to fashion curation, and how has your understanding of the role of a curator shifted since your earliest exhibitions?

I studied architecture and wanted to put that together with my interest in fashion’s histories. I have always, therefore, thought of the role of the curator as absolutely embedded within the exhibition space. I guess how it has changed over the years is that I have had the great fortune of having staged exhibitions in many different spaces and countries and have developed a more nuanced practice. I used to be scared of mannequin wigs and props, whereas now I feel excited by the details and collaborative commissions that can be embedded in a project.

How has your approach to storytelling through clothing evolved over the years, and what continues to excite you about this field?

I love the discipline of exhibiting fashion as much as I did 30 years ago. It never exhausts itself for me and fortunately the context has changed. At first it was about making a case for fashion exhibitions, now as many more people recognise it as a distinct field of research it can be politicised more. It can not only say “dress is important” or “this is how dress evolved”; it can ask questions of the fashion industry.

I:01 APRONS residency workshop at Chelsea Space, Chelsea College of Arts (2025). Photo: Kit Lovelock. Courtesy of University of the Arts London

It seems like we are seeing a renewed interest in utilitarian garments, including aprons, on runways and in cultural conversations. Why do you think fashion is returning to function and workwear aesthetics at this moment?

Utilitarian fashion [like all fashions] come and go in cycles. What has been fantastic about looking at aprons and the relationship with fashion, is how it migrates from being a decorative panel, showing flourishes of embroidery, to a protective layer, to a pocket on a ribbon, to a fragment for the Avantgarde to experiment with. And then there is the greater persistence of course with aprons tailor made for specific trades that, given the choreographed nature of the craft, remains more constant.

The apron is a multifaceted garment, connected to domestic life, creativity, and labour. What surprised you most in your research or collaboration with Carol Tulloch about the ways aprons carry meaning across different communities?

The apron spans so many cultures and communities and the workshops we have been running during the residency at Chelsea Space has confirmed this. We have spoken a lot about domesticity, how it has been represented and under-represented in the museum, the apparent modesty of some of the aprons we have studied and their extraordinary power. We have also studied an apron that was de-accessioned from the V&A - this tells us something.

Toby Glanville Cheesemaker Dorset, 1994

This project resists treating the apron as merely nostalgic. How do you balance sentiment with critical analysis when presenting garments that have personal and cultural resonance?

Nostalgia hovers around aprons. There is a picture of a, perhaps lost, domestic space that has been hugely problematic, but that is a powerful carrier of memory. I think it is about repetition. People tend to change their clothes, but aprons are personal. Their use is ritualised, and they carry the stains of everyday life.

Given how much of fashion curation intersects with broader cultural narratives, race, class, gender, how do you see the industry adapting (or struggling) to engage more deeply with these layered conversations?

Carol Tulloch, who is a professor of dress, diaspora and transnationalism at Chelsea College of Arts, and I have been friends and colleagues for 25 years and the context in which we have worked together has changed seismically in that time. Fashion - about identity, about performativity, about sustainability, about the confluence of cultural systems and hierarchies - is now an area of research that can lead multiple debates. Museums are cumbersome institutions and so the projects for necessary change need to be made more reactive. Both Tulloch and I believe in temporary exhibitions to address this.

As the residency concludes with the publication launch, what do you hope people will take away from this project about the apron?

I guess it is about multiple readings of the apron. We have been incredibly delighted at the interest around this project. From community projects that are inspired by the workshops, to supporting individual researchers, to creating a collection that will be accessible within the BA (Hons) Textile Design course at Chelsea College of Arts, part of University of the Arts London (UAL). We have been clear all along that this wasn’t to be seen as an exhibition, but notes that document curatorial processes and exhibition-making considerations. I have brought mobile structures from my studio upon which to test material in 3D and the small publication is like a fold out map that contains the references we have been quoting along the way: from exquisite portraits of tradespeople by Toby Glanville, and Syd Shelton, a short story by Lydia Davis, books on whitework, the history of dress.

Website: judithclarkstudio.com

Instagram: @prefigured_

Narinder Sagoo MBE, Senior Partner at Foster + Partners and renowned architectural artist, has embarked on an ambitious new personal project in support of Life Project 4 Youth (LP4Y), a charity that works towards the upliftment of young adults living in extreme poverty and suffering from exclusion. Narinder has been an ambassador for LP4Y since 2022…

Charlotte Winifred Guérard is a London-based artist and recent graduate of the Royal Academy of Arts School, where she was recognised as a Paul Smith’s Foundation scholar for her artistic achievement. Her work has been exhibited at the Royal Academy, Coleman Project Space, Fitzrovia Gallery, Messums and Palmer Gallery, and she has completed prestigious residencies including…

BBC Radio 1 presenter, DJ, podcaster, and award-winning entrepreneur Jaguar joined us for our In conversation with series to discuss her journey from sneaking out to raves on the tiny island of Alderney to becoming a tastemaker in the UK dance scene, her debut EP flowers…

Annie Frost Nicholson is an artist whose work sits at the electric intersection of personal memory, public ritual and emotional release. Known for transforming private grief into bold, colour-saturated experiences - from stitched paintings to micro-discos - Annie’s practice creates space for collective healing without losing the rawness of its origins…

We spoke to visionary director Łukasz Twarkowski ahead of the UK premiere of ROHTKO, a groundbreaking production that takes inspiration from the infamous Rothko forgery scandal to ask urgent questions about originality, truth and value in art today. Combining theatre, cinema, sound and digital technology, the work challenges…

Iranian-born British curator and producer Tima Jam is the Founder of Art Voyage, a new migrant-led cultural platform committed to building a dynamic, equitable, and globally connected arts ecosystem through novel initiatives comprising exhibitions, public art, summits, residences, and community engagement to create a lasting cultural and social impact…

Betty Ogundipe (b. 2001) is a multidisciplinary artist of Nigerian heritage whose work explores resilience, femininity, and the power of love and resistance. Her debut solo exhibition, LOVE/FIGHT at Tache Gallery…

Absolut Vodka celebrated the launch of its Keith Haring Artist-Edition bottle with a public art takeover, transforming London’s Charing Cross station into “Haring Cross” on 17–18 September. We spoke with Deb Dasgupta, Absolut’s Vice President of Global Marketing…

Maya Gurung-Russell Campbell is an artist working across sculpture, image, and text, exploring personal and collective memory. She is currently studying at the Royal Academy Schools (graduating 2026) and holds a BA in Photography from the London College of Communication…

YARA + DAVINA make social practice artwork, creating ambitious public artworks that respond to site, context and audience. Unfailingly inventive, they use formats from within popular culture to make works which are accessible and playful…

Benni Allan is the Founding Director of EBBA Architects, a London-based studio recognised for its ambitious, cross-disciplinary approach that bridges architecture, culture, fashion and design. Benni founded EBBA to unite his passion for architecture, making and collaborative practice. In this interview, Benni discusses EBBA’s ethos and Pulse, a new installation commissioned for Houghton Festival at Houghton Hall…

Oskar Zięta is an architect, process designer and artist whose work challenges the boundaries between disciplines. His practice brings together design, engineering, art and bionics to create sculptural forms. His latest installation, ‘Whispers’, is currently on display outside One New Ludgate as part of the London Festival of Architecture 2025…

Danny Larsen is a Norwegian artist who has transitioned from a successful career in professional snowboarding to establishing himself as a distinctive painter. His detailed neo-pointillist landscapes reflect a deep connection to nature and a personal journey of transformation. Ahead of his debut London solo exhibition…

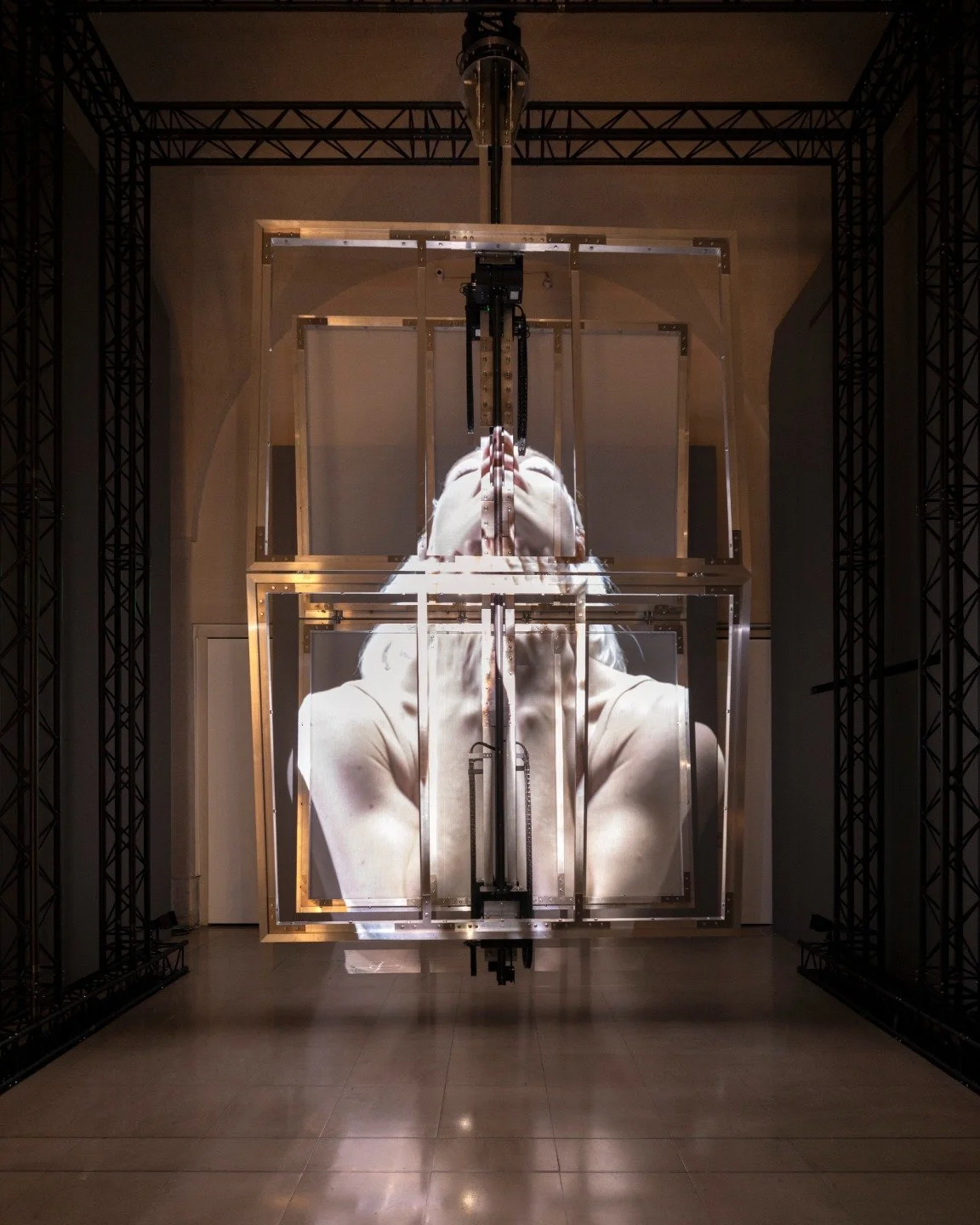

Nimrod Vardi and Claudel Goy, directors of arebyte Gallery, discuss how the space is redefining digital art by blending technology, social science, and immersive experiences. From AI and consciousness to the societal impact of tech, arebyte’s bold exhibitions go beyond visual spectacle, focusing on meaningful engagement and innovative presentation…

Varvara Roza is a London-based private art advisor and artist representative. She specialises in promoting contemporary art by both established and emerging international artists. In our conversation, we discussed her unique approach to the art market…

David Ottone is a Founding Member of Award-winning Spanish theatre company Yllana and has been the Artistic Director of the company since 1991. David has created and directed many theatrical productions which have been seen by more than two million spectators across 44 countries…

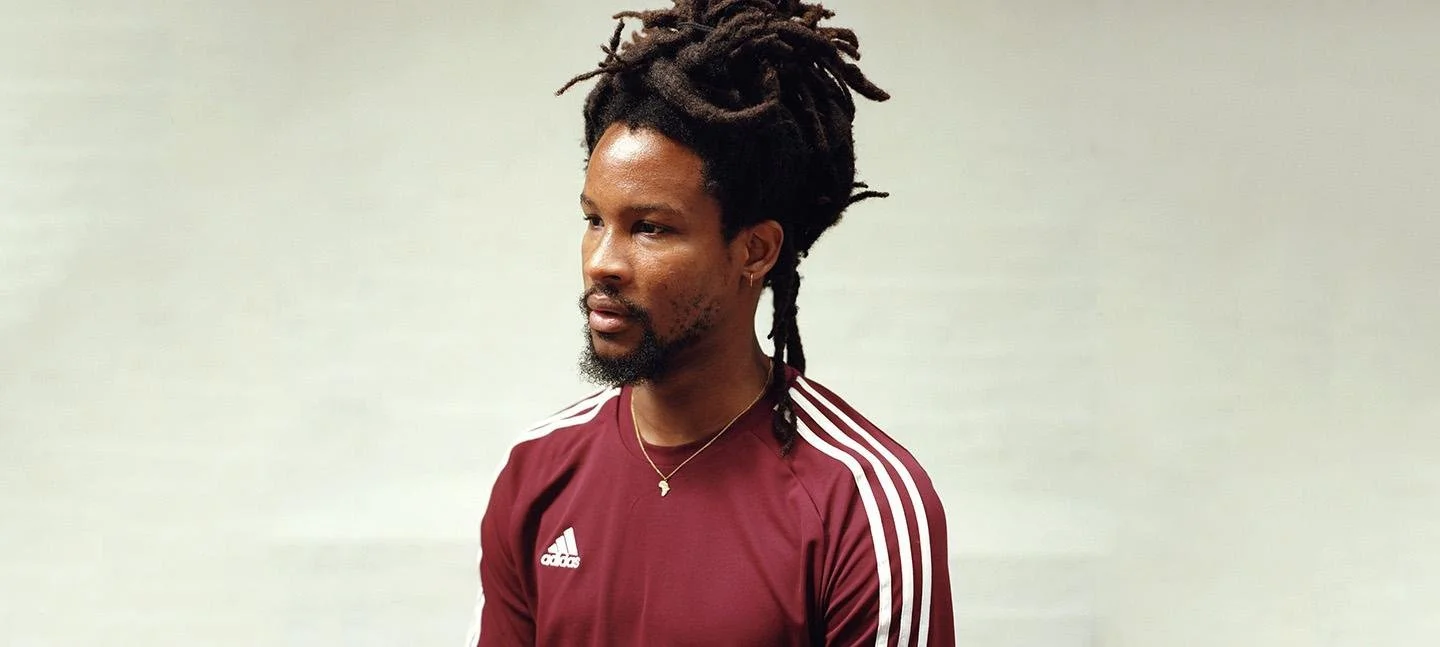

Akinola Davies Jr. is a BAFTA-nominated British-Nigerian filmmaker, artist, and storyteller whose work explores identity, community, and cultural heritage. Straddling both West Africa and the UK, his films examine the impact of colonial history while championing indigenous narratives. As part of the global diaspora, he seeks to highlight the often overlooked stories of Black life across these two worlds.

Gigi Surel is the founder of Teaspoon Projects, a groundbreaking cultural initiative launching in London with its first exhibition and programme. Dedicated to exploring contemporary storytelling, Teaspoon Projects blends visual arts and literature while encouraging audience participation through carefully curated events.

Dian Joy is a British-Nigerian interdisciplinary artist whose work delves into the intersections of identity, digital culture, and the fluid boundaries between truth and fiction. Her practice is rooted in examining how narratives evolve and shape perceptions, particularly in the digital age.

Youngju Joung is a South Korean artist known for her paintings of shanty village landscapes, illuminated by warm light. Inspired by memories of her childhood in Seoul, she uses crumpled hanji paper to create textured, lived-in spaces that reflect both poverty and affluence.

John-Paul Pryor is a prominent figure in London’s creative scene, known for his work as an arts writer, creative director, editor, and songwriter for the acclaimed art-rock band The Sirens of Titan…

Poet and novelist Hannah Regel’s debut novel, The Last Sane Woman, is a compelling exploration of the emotional lives of two aspiring artists living at different times, yet connected by the discovery of a box of letters in a forgotten feminist archiv…

Daria Blum, a 2023 RA Schools graduate, won the inaugural £30,000 Claridge’s Royal Academy Schools Art Prize in September. Her exhibition, Drip Drip Point Warp Spin Buckle Rot, at Claridge’s ArtSpace...

We recently interviewed Eden Maseyk, co-founder of Helm, Brighton’s largest contemporary art gallery, which has quickly established itself as a thriving cultural hub…

Lina Fitzjames is a Junior Numismatist at Baldwin’s Auction House, located at 399 Strand. She is part of a new generation reshaping the image of numismatics, the study of coinage….

Sam Borkson and Arturo Sandoval III, the acclaimed LA-based artists behind the renowned collective "FriendsWithYou," are the creative minds behind "Little Cloud World," now on display in Covent Garden. During their recent visit to London, we had the privilege of speaking with them about their creative process and the inspiration behind this captivating project.

Paul Robinson, also known as LUAP, is a London-based multimedia artist renowned for his signature character, The Pink Bear. This character has been featured in his paintings, photography, and sculptures, and has travelled globally, experiencing both stunning vistas and extreme conditions…

Koyo Kouoh is the Chief Curator and Executive Director of Zeitz MOCAA…

Matilda Liu is an independent curator and collector based in London, with a collection focusing on Chinese contemporary art in conversation with international emerging artists. Having curated exhibitions for various contemporary art galleries and organisations, she is now launching her own curatorial initiative, Meeting Point Projects.

Lily Lewis is an autodidact and multidisciplinary artist working in the realms of the narrative, be that in the form of a painting, a poem, large scale sculptures, tapestry, or performance…

With Six Nations 2026 starting on 5 February, London is packed with pubs, bars and restaurants showing every match…

This week brings fresh details from some of the UK’s most anticipated exhibitions and events, from Tate Modern’s Ana Mendieta retrospective and David Hockney’s presentation at Serpentine North to the British Museum’s acquisition of a £35 million Tudor pendant…

This week in London (2–8 Feb 2026) enjoy Classical Mixtape at Southbank, Arcadia at The Old Vic, Kew’s Orchid Festival, Dracula at Noël Coward Theatre, free Art After Dark, Chadwick Boseman’s Deep Azure, the Taylor Wessing Portrait Prize, and Michael Clark’s Satie Studs at the Serpentine…

SACHI has launched a limited-edition Matcha Tasting Menu in partnership with ceremonial-grade matcha specialists SAYURI, and we went along to try it…

Croydon is set to make history as the first London borough to host The National Gallery: Art On Your Doorstep, a major free outdoor exhibition bringing life-sized reproductions of world-famous paintings into public spaces…

February in London sets the tone for the year ahead, with landmark exhibitions, major theatre openings, late-night club culture and seasonal festivals taking over the city. From Kew’s 30th Orchid Festival to Tracey Emin at Tate Modern and rooftop walks at Alexandra Palace, here’s what not to miss in February 2026…

Tate Modern has announced that Tarek Atoui will create the next Hyundai Commission for the Turbine Hall. The artist and composer is known for works that explore sound as a physical and spatial experience…

Kicking off the London art calendar, LAF’s 38th edition at Islington showcased a mix of experimental newcomers and established favourites. Here are ten standout artists from London Art Fair 2026…

Discover a guide to some of the artist talks, as well as curator- and architecture-led discussions, to be on your radar in London in early 2026…

This week in London, not-to-miss events include the T.S. Eliot Prize Shortlist Readings, the final performances of David Eldridge’s End, the return of Condo London, new exhibitions, classical concerts, a film release, creative workshops, wellness sessions, and a standout food opening in Covent Garden with Dim Sum Library…

Plant-based cooking gets the Le Cordon Bleu treatment in a new series of London short courses…

January is your final opportunity to catch some of London’s most exciting and talked-about exhibitions of 2025. Spanning fashion, photography, contemporary sculpture and multimedia, a diverse range of shows are drawing to a close across the city…

As the new year begins, London’s cultural calendar quickly gathers momentum, offering a packed programme of exhibitions, festivals, performances and seasonal experiences throughout January. Here is our guide to things you can do in London in January 2026…

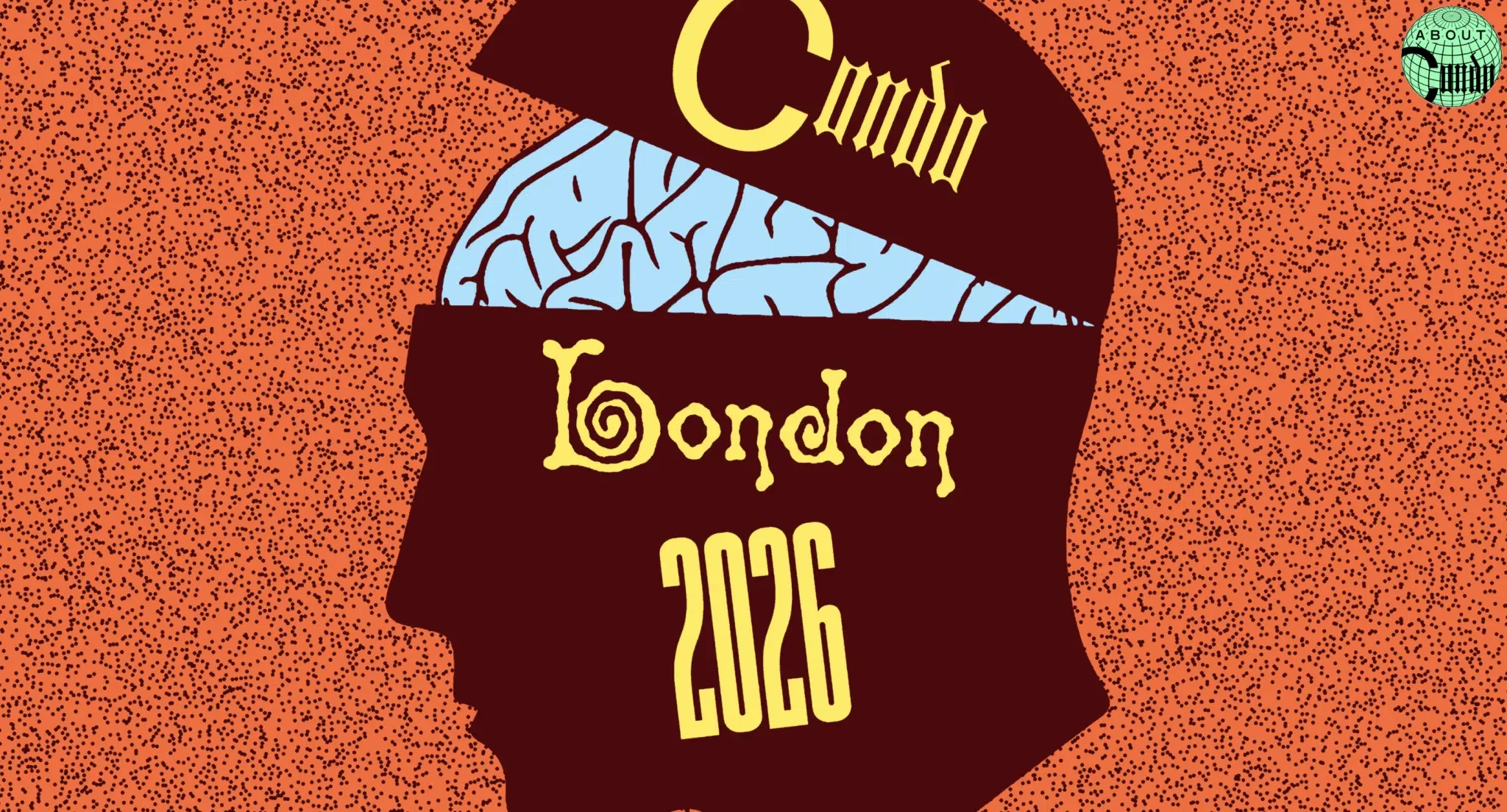

Condo London returns in January 2026 as a city‑wide, collaborative art programme unfolding across 50 galleries in 23 venues throughout the capital, from West London and Soho to South and East London. This initiative rethinks how contemporary art is shown and shared, inviting London galleries to host international…

The Southbank Centre has announced Classical Mixtape: A Live Takeover, a one-night-only, multi-venue event taking place in February 2026, bringing together more than 200 musicians from six orchestras across its riverside site…

This week in London features late-night Christmas shopping on Columbia Road, festive wreath-making workshops, live Brazilian jazz, mince pie cruises, theatre performances, art exhibitions, a Christmas disco, and volunteering opportunities with The Salvation Army.

Discover London’s unmissable 2026 fashion exhibitions, from over 200 pieces of the late Queen’s wardrobe at The King’s Gallery to the V&A’s showcase of Elsa Schiaparelli’s avant-garde designs and artistic collaborations…

Marking her largest UK project to date, Sedira’s work will respond to the unique architectural and historical context of the iconic Duveen Galleries, offering audiences an experience that merges the political, poetic, and personal…

This week in London, enjoy festive events including Carols at the Royal Albert Hall, LSO concerts, designer charity pop-ups, late-night shopping, art exhibitions, film screenings, foodie experiences, last-chance shows, and volunteer opportunities across the city…

Explore Belgravia this Christmas with a festive pub crawl through London’s most charming historic pubs, from The Grenadier’s cosy mews hideaway to The Nags Head’s quirky classic tavern…

From the joys of Christmas at Kew to the lively Smithfield meat auction, and from major concerts and ballets to intimate workshops and family-friendly trails, the city offers an extraordinary mix of experiences. This guide brings together the very best of Christmas in London…

This guide highlights some of the must-see art exhibitions to visit over the festive period in London, including the days between Christmas and New Year’s. From major retrospectives of international masters such as Kerry James Marshall, Wayne Thiebaud, and Anna Ancher, to engaging contemporary works by Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, Jennie Baptiste, and Tanoa Sasraku…

London’s cultural scene, a gallery or museum membership is the perfect alternative to another pair of socks. From unlimited access to exhibitions and exclusive events to discounts in shops and cafés, these memberships offer experiences that can be enjoyed throughout the year, while also supporting the vital work of arts organisations…

Your guide to London’s can’t-miss events this week, 17–23 November 2025, from Cabaret Voltaire live at ICA to Ballet Shoes at the National Theatre and The Evolution of UK Jazz at the Barbican…

Charlotte Winifred Guérard is a London-based artist and recent graduate of the Royal Academy of Arts School, where she was recognised as a Paul Smith’s Foundation scholar for her artistic achievement. Her work has been exhibited at the Royal Academy, Coleman Project Space, Fitzrovia Gallery, Messums and Palmer Gallery, and she has completed prestigious residencies including…

This week in London, you can enjoy festive ice skating, Christmas lights, jazz and classical concerts, and a range of art exhibitions. Highlights include Skate at Somerset House, Christmas at Kew, the EFG Jazz Festival, and the Taylor Wessing Photo Portrait Prize 2025…

From the 6th to the 9th of November, the leading West African art fair Art X Lagos celebrates its 10th birthday at the Federal Palace on Victoria Island. Founded by Tokini Peterside-Schwebig in 2016, the fair has become an unmissable event in the global art calendar, attracting galleries from over 70 countries and participants from 170 countries since its launch…