Jura Skye: Between Form, Sound and Feeling

My first introduction to Jura Skye was at Emanuel von Baeyer Gallery, for a one-night event titled Synesthesia. As the name suggests, guests were treated to an experience that sat somewhere between art and music, prompting us all to question the very boundaries between them. At the heart of the exhibition was Ræu, one of Skye’s alluring tapestries. Throughout the evening, Skye and his collaborators proceeded to reverse engineer artworks from the gallery’s exhibition, Walter Sickert and His Circle, into sound. I would be hard-pressed to define the night as a concert, an exhibition, or even a performance. It was certainly a powerful experience, and one that fuelled my curiosity about Skye’s multi-faceted practice.

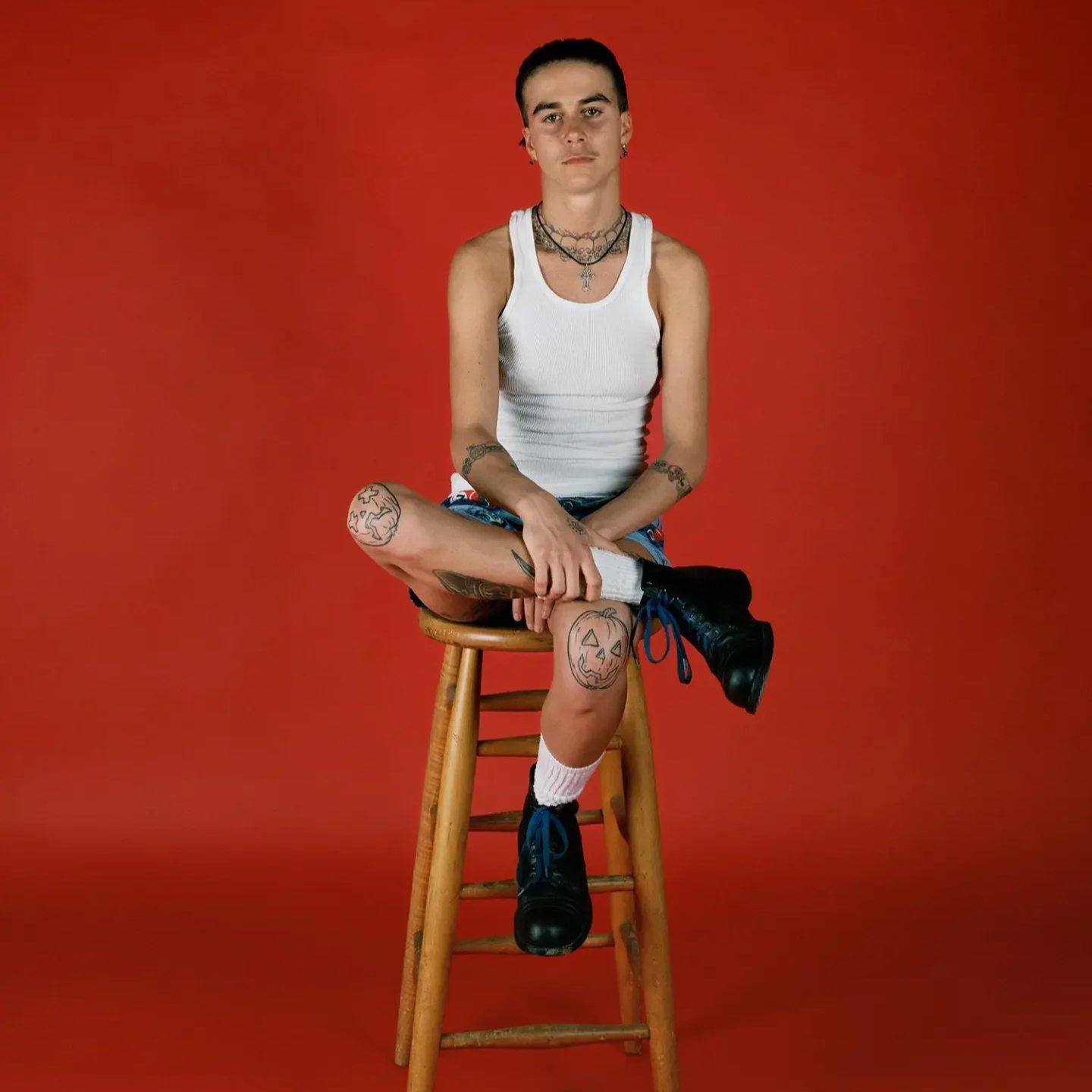

Image credit Evgeniya Negrebetskaya.

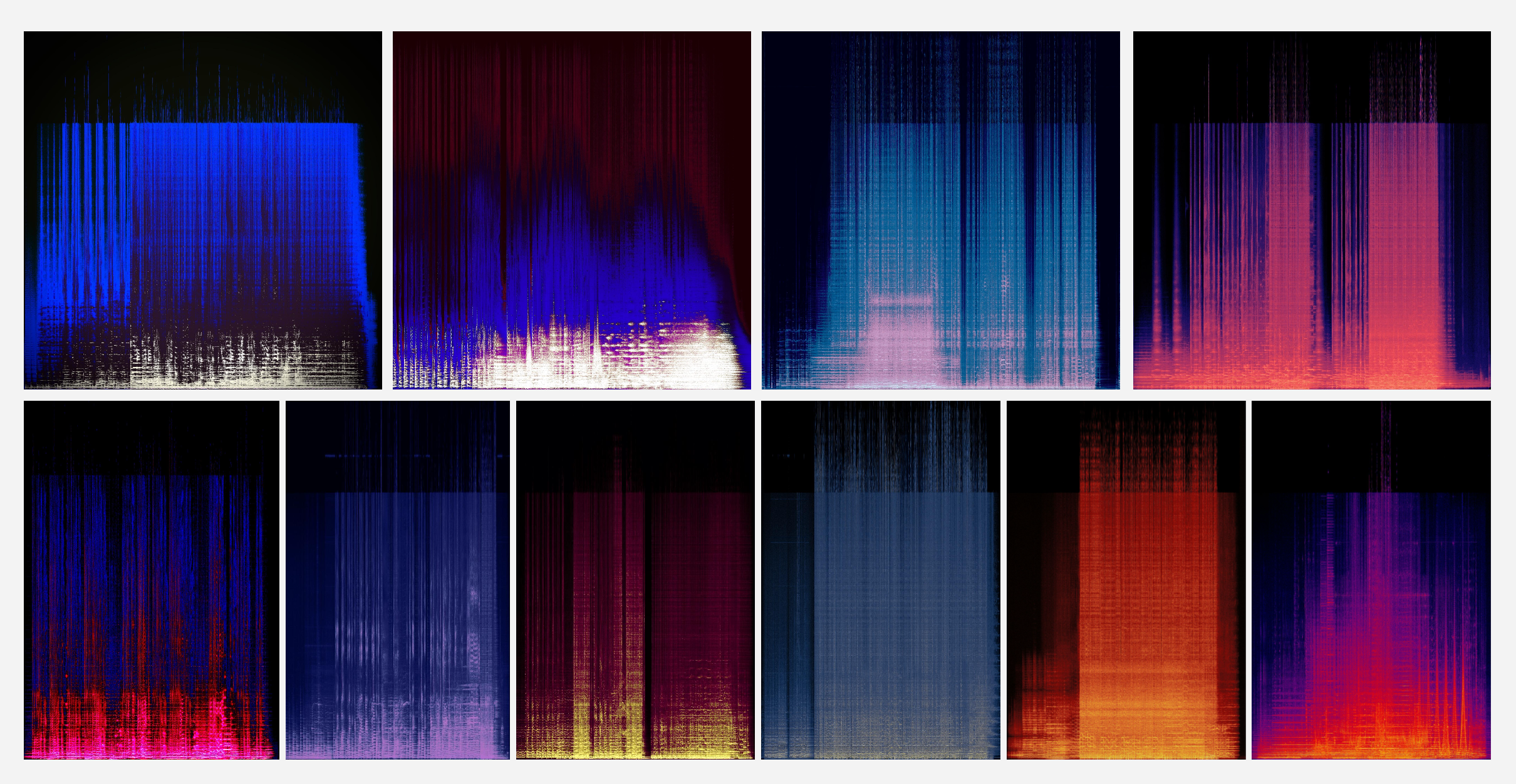

Bringing material life to sound is an ongoing passion for Skye, whose debut album Nothing exists across both genres. Each song has been painstakingly rendered by the artist as a tapestry through the use of spectrogram technology. Skye uses spectrograms to map frequencies over a period of time, analysing his own compositions and resulting in a visual record that is at once abstracted yet fundamental to the original sound. Originality is a word that strikes a deep chord when considering Skye’s practice, which draws on diverse cultural influences and a diverse background of his own.

Born in Moscow, Skye trained in the modern-classical division of the celebrated Moscow Conservatory. There, he became frustrated by the scientific approach to music which was prevalent, in which the technical was prioritised over and at the expense of emotional resonance. This led Skye to forge his own path, a path unexpectedly enlightened by the guidance of Russian anthropologist Konstantin Kuksin. Through anthropology, and in particular investigating nomadic cultures and their relationships to sound, he was able to reconnect with the emotional potency of music. He also developed a new appreciation for its cultural rootedness, observing how instruments were crafted from the land and formed a much larger part of everyday life than he was used to. In addition to its entertainment value, music was one of several key ways in which these societies preserved and retold their heritage. In this way, Skye came to realise, textiles such as rugs and carpets played a similar role. It was in this unlikely observation that the seeds of Nothing were born.

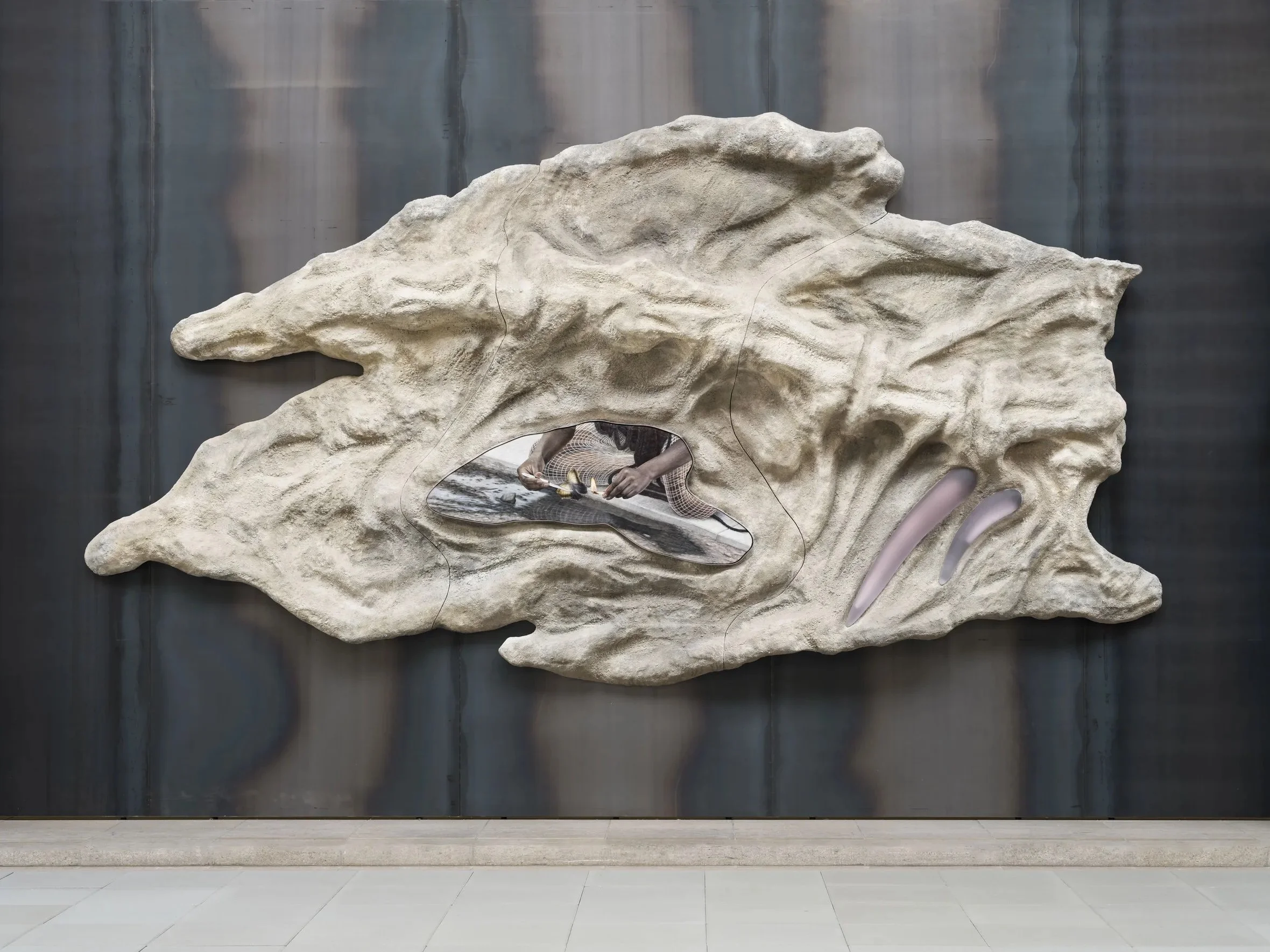

The 11 tapestries in Jura Skye’s Nothing. Image courtesy of Jura Skye.

It is perhaps unsurprising that Skye found so much inspiration in this nomadic research, as he himself experienced a significant upheaval in 2022 when he left home with his family and moved to London. Upon listening to Nothing, I sense hints of transience and nostalgia, alongside an underlying embrace of experimentation and the unknown. There are moments which feel discordant and even jarring, but those ruptures enable new patterns of sound to emerge. These patterns are then made visible, quite literally, by the accompanying tapestries. The very act of mapping introduces new and nuanced spatial dimensions to the project, simultaneously offering a visual interpretation of the tracks, while feeding back into the listener’s experience of the original sounds.

Jura Skye with fellow musicians Dan Kert (Plastic Barricades) and Riverloop (Ilya Permaykov).

In London, often cited as the most multicultural city in the world, nothing makes sense. So many of us carry personal and familial stories of migration, and so many of us are craving connection and creative inspiration. It is no wonder that Synesthesia found an enraptured audience here, nor that Skye has connected with so many local collaborators to explore ideas of place and belonging. A sneak preview of the artist’s next project, Return to Trees, feels like a natural yet innovative extension of his practice. Through the use of geophones, Skye has been able to capture subterranean recordings of trees which are then integrated with real human voices in a truly special exploration of the sonic connection between us and the landscape. I can’t help but conclude: we need artists like Skye to reveal and restore these points of connection, while we still can.

To experience Jura Skye’s Nothing album for yourself and keep up with upcoming projects, visit his Website, Instagram and Spotify.

Words by Sofia Carreira-Wham

FLO spent an evening with Special Guest, speaking to the host, Eve, and some of the night’s speakers to find out what draws people to the stage and what keeps the crowd coming back…

As March brings the first signs of spring to London, a number of exciting art exhibitions are opening across the city. Tate Britain will host the first major solo exhibition of British artist Hurvin Anderson, Dulwich Picture Gallery presents the first UK show of Estonian modernist Konrad Mägi, and the much-anticipated exhibition dedicated to influential Italian designer Elsa Schiaparelli…

The Ivy Collection has partnered with Papa Salt Gin to celebrate unsung heroines this International Women’s Day. From Wednesday 11 February 2026, people across the United Kingdom and Ireland are invited to nominate inspiring women in their communities who deserve recognition for their selfless contributions…

We recently spoke with Dr Georgina Portelli, Vice Chair of Malta International Contemporary Arts Space (MICAS), about the vision and development of Malta’s major new contemporary art institution. Built within the historic 17th-century Floriana bastions on the edge of Valletta…

Albers is a contemporary neighbourhood bistro in De Beauvoir Town, offering far more than its modest claim of serving “Quite Good Grub”. Tucked just off the bustle of Kingsland Road, it combines relaxed, understated interiors with confident, thoughtfully prepared dishes…

A wonderful alpine-style chalet tucked into the courtyard of the Rosewood London in Holborn. From the moment you step inside, the outside world seems to melt away, replaced by warmth, intimacy and a sense of escapism that feels far removed from central London…

Lakwena Maciver is a London-based artist known for her use of colour and text, and for public artworks that bring a sense of connection to everyday spaces….

Gilroy’s Loft is a newly opened Seafood Restaurant in Covent Garden situated at the rooftop of the Guinness Open Gate Brewery London which was officially opened by none other than King Charles in early December…

Ted Hodgkinson is Head of Literature & Spoken Word at Southbank Centre and oversees the seasonal literature programme as well as the annual London Literature Festival. He has judged awards including the BBC National Short Story Award and the Orwell Prize for political writing, and in 2020 he chaired the International Booker Prize…

Narinder Sagoo MBE, Senior Partner at Foster + Partners and renowned architectural artist, has embarked on an ambitious new personal project in support of Life Project 4 Youth (LP4Y), a charity that works towards the upliftment of young adults living in extreme poverty and suffering from exclusion. Narinder has been an ambassador for LP4Y since 2022…

This week in London (26 Jan – 1 Feb 2026), catch theatre at Malmaison Hotel, live Aphex Twin performances at Southbank, art exhibitions at Barbican, ICA, and Goldsmiths CCA, comedy at Sadler’s Wells, plus music, cinema, and new foodie spots like Le Café by Nicolas Rouzaud.

Discover a guide to some of the art exhibitions to see in London in February 2026, including the much-anticipated Tracey Emin and Rose Wylie exhibitions at Tate and the Royal Academy of Arts respectively; works by artists Aki Sasamoto and Stina Fors at Studio Voltaire; the third edition of the Barbican’s Encounters series with Lynda Benglis; an Isaac Julien world premiere at Victoria Miro…

This week in London includes the London Short Film Festival, Winter Lights at Canary Wharf and London Art Fair, plus new exhibitions by Georg Baselitz, Mario Merz and Umi Ishihara. Also on are performances at the Southbank Centre, Burns Night celebrations, last chances to see Dirty Looks at the Barbican, and the opening of Claridge’s Bakery…

Just off Bermondsey Street, a short stroll away from London Bridge, is Morocco Bound Bookshop. Independent bookshop by day, lively venue by night this place is one of London’s hidden gems…

Bistro Sablé looks as French as it tastes. The 65-seater lateral restaurant is spread across two areas wrapping around the central bar…

London’s plant-based dining scene is more exciting, diverse and delicious than ever. From Michelin-starred tasting menus where vegetables take centre stage, to relaxed neighbourhood favourites and casual spots…

From bold new works by leading choreographers to iconic operas reimagined for modern audiences, The Royal Ballet and The Royal Opera continue to define London’s cultural scene. With tickets starting at just £9, here is your guide to the unmissable performances of 2026…

From explorations of queer life, diasporic memory, and American urban history to inventive contemporary approaches, this guide provides an overview of the most anticipated photography exhibitions in London this year…

This January, discover London’s most exciting art exhibitions, from emerging talents and debut solo shows to major museum highlights…

Seeds of Hate and Hope at the Sainsbury Centre, Norwich, is a powerful exhibition examining how violence, ideology and trauma are created, spread and remembered…

This week in London features late-night Christmas shopping on Columbia Road, festive wreath-making workshops, live Brazilian jazz, mince pie cruises, theatre performances, art exhibitions, a Christmas disco, and volunteering opportunities with The Salvation Army.

Maggie Jones’s is back and the residents of Kensington and their regulars will be thrilled. The restaurant, tucked away off Kensington Church Street, is a slice of London lore. In the 1970s, Princess Margaret and Lord Snowdon were such devoted regulars that the staff referred to her under the alias “Maggie Jones”….

Afra Nur Uğurlu is a visual artist and recent London College of Communication graduate whose practice bridges beauty, fashion, art, and cultural studies. In this interview, we discuss Hinterland, her zine exploring how the Turkish diaspora navigates and challenge es dominant representations…

A poignant review of two debut exhibitions curated by Yiwa Lau, exploring memory, community, and our emotional ties to place, from London’s overlooked moments to a disappearing village near Beijing.

The Lagos International Theatre Festival 2025 (LIFT) kicked off in spectacular fashion at the Muson Centre on 14th November. The star-studded opening night featured electrifying theatre, music, dance, and even an impromptu rap freestyle from Lagos Governor, Mr. Sanwo-Olu…

Miami Art Week 2025 transforms the city into a global art hub, featuring Art Basel, Design Miami, top fairs, museum exhibitions, and pop-ups. From established galleries to emerging artists and installations, the week offers a dynamic snapshot of contemporary creativity across Miami Beach, Wynwood, Downtown, and the Design District…

Here is our guide to Christmas gifts you can buy at London gallery shops, to help you find presents for loved ones, friends, or a Secret Santa at the office. From The Courtauld to the National Gallery, every purchase helps fund exhibitions…

From historic toyshops and independent markets to avant-garde boutiques and curated art book shops, these locations showcase creativity, charm, and festive spirit, making Christmas shopping in London a truly enjoyable experience…

Townsend Productions is marking the 50th anniversary of the Grunwick Strike (1976–1978) with the return of We Are the Lions, Mr Manager!, a powerful play written and musically directed by Neil Gore and directed by Louise Townsend. The production features Rukmini Sircar as Jayaben Desai. Ahead of the London run, we spoke to Neil Gore and Rukmini Sircar…