In conversation with Afra Nur Uğurlu

“By the end of it, I was so tired. I thought to myself, what a privilege it is. Like, I can take these off. I can put these on, and I can take these off, right?”

- Afra Nur Uğurlu

Afra Nur Uğurlu. Image courtesy of Afra Nur Uğurlu

Afra Nur Uğurlu is a visual artist and recent London College of Communication graduate whose practice bridges beauty, fashion, art, and cultural studies. In this interview, we discuss Hinterland, her zine exploring how the Turkish diaspora navigates and challenges dominant representations. Using the freedom of independent publishing, Afra reclaims the means of visual storytelling to interrogate power, identity, and the politics of seeing. This conversation offers insight into the creative, emotional, and cultural foundations of Hinterland, and the wider questions it raises about belonging and representation.

How did the form of a zine allow you to explore and express yourself in the creation of this work?

Hinterland was, or is, an exploration of culture and power and the dynamics within that. The zine format felt like the most natural way to like to display these themes because of its freedom and intimacy.

When you look into independent publishing, that's what allows me to take back the narrative, reclaim the means of production, because nobody else is involved within that. As an extension of that, to reclaim the ways of representing oneself. And so, I thought that the zine was a fitting format, without the constraints of traditional publishing.

It makes space for multiple voices and textures, whether on an emotional basis or, culturally, visually. Within this study of work, it just all coexists as one. The main thing was to reclaim the means of representation, through collage and a bit of satire. There’s a bit of exaggeration as well. It depends on how you read it and how you take it.

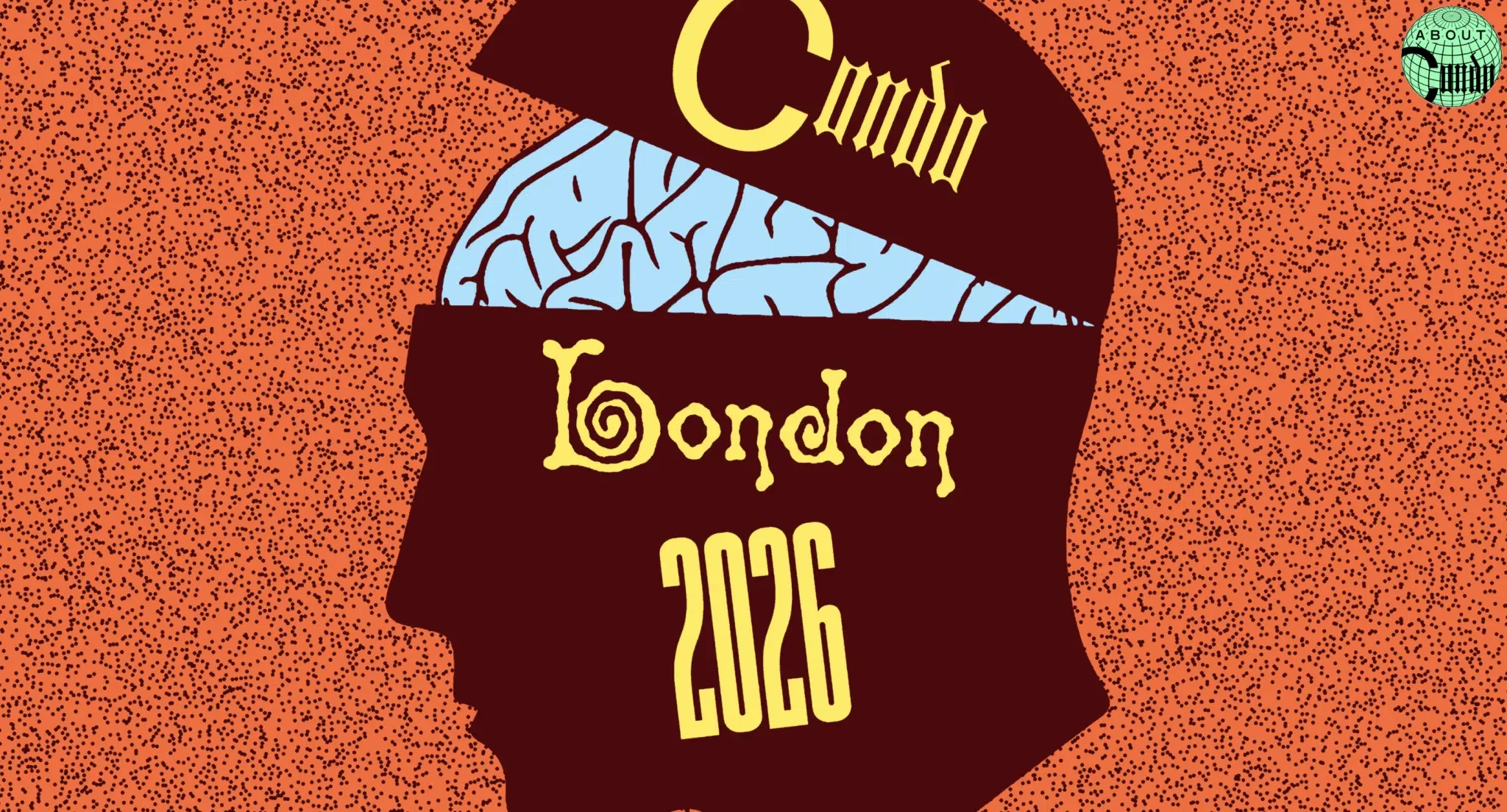

Hinterland cover

There's a real power in that, in that belief and that conviction just to do it for oneself, taking the means of production and representation into your own hands.

It’s not my place to judge upon whether did a great job of representing other people's voices. Hence why I have two parts of the zine, the first parts being personal work, and then the second part, I included collaborators and anybody that felt thematically attached.

So it, it was an interesting dynamic, because I was researching specific demographics that I also then wanted to cater to. So, it was about and for, this specific demographic. Again, back to zines, I didn't want it to be super black and white and very serious. I wanted it to be digestible and like, who says you can't have fun?

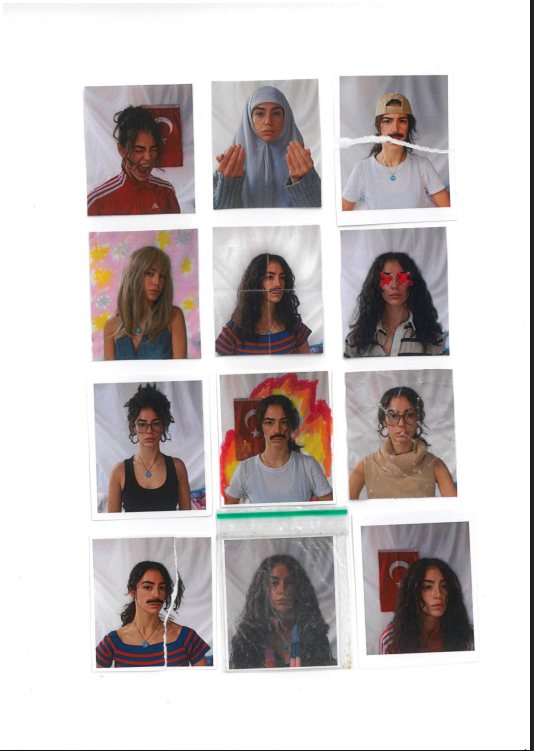

Borderlines. Concept and Photography by Afra Nur Uğurlu. Creative Direction by Gizem Kahraman. Modelling by Bismah Sharrif. Hair and Make Up Artistry by Naemi Kämpfer. Styling by Jana Grinchenko

I was going to ask that. Did you have fun making this zine? It seems so, but I'm sure you encountered a lot of emotions through the process. How did it go?

It being a zine was perfect for me because I could jump from chapter to chapter, topic to topic, project to project. It was fun. But I think the fun part only came after I saw it all coming together. It was during a time when I was struggling emotionally. Working on Hinterland really forced me to dive deeper into… I don't know if I want to say generational trauma, but the ways that I grew up, and the ways that I neglected my identity. Things from the past that I thought I had forgotten I had come up against. So, it was quite emotional. It was really hard.

It just goes to show how much, not only power this topic holds for so many people, but also that there's nuances within it, and you can display something in a fun and satirical way but also see the complexity and the seriousness behind it.

How long did it take, by the way?

It took me... I don't know, how long did it take me? Maybe a month. With the research, and all of that. For me, it was vital to fully understand the context, even if you're part of a specific community. When speaking about power dynamics within cultural studies, you can fall into that dynamic yourself, even as being part of the diaspora.

Borderlines. Concept and Photography by Afra Nur Uğurlu. Creative Direction by Gizem Kahraman. Modelling by Bismah Sharrif. Hair and Make Up Artistry by Naemi Kämpfer. Styling by Jana Grinchenko

And so, I didn't want to do anything wrong. I was worried and wary when it came to the curational aspect of the zine to not speak for or on behalf of others. Because, at the end of the day, I had the means of curation. So, power plays into that as well. I was looking into power and then also realized how much power I had in all of this. It was scary. It was all sorts of things.

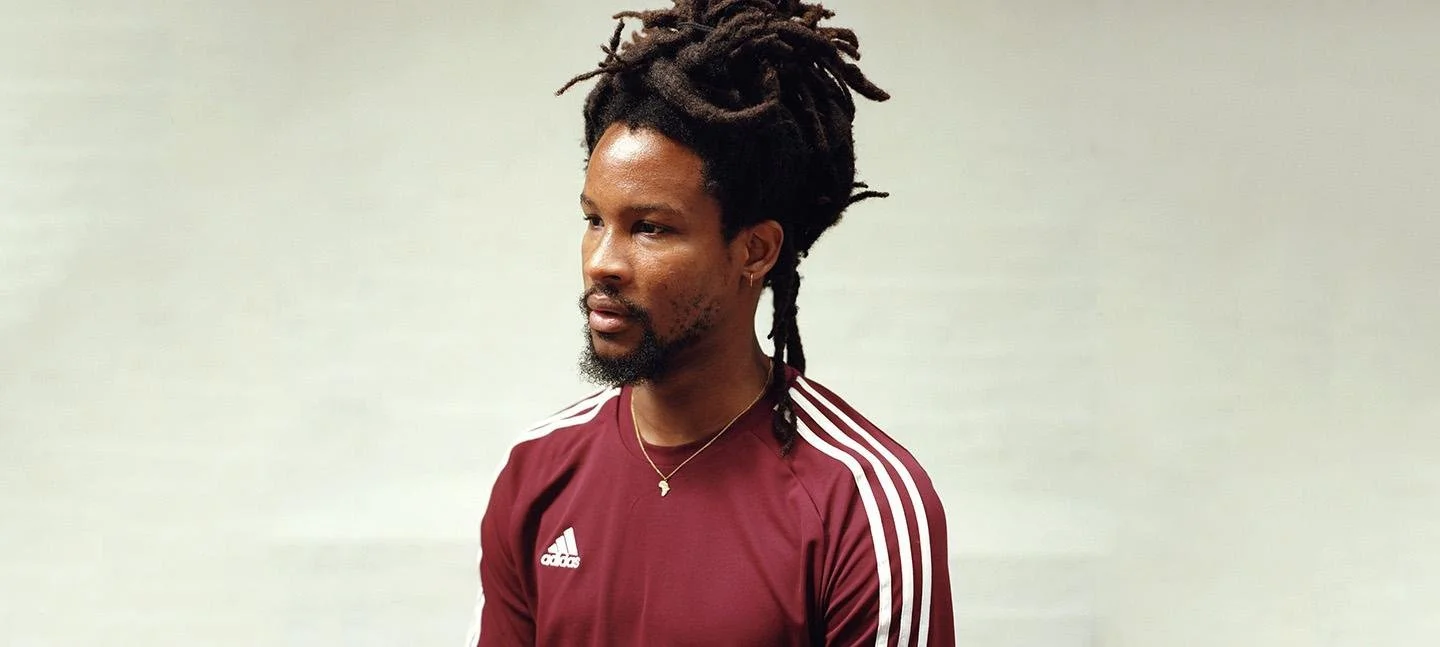

What did it mean to you to collaborate with these two artists, Deniz-Can Sayim and Yusuf Arslan?

You have to take into account that there is going to be other people that have something to say and something to include. I can speak to people, and I can do my research as much as I can and want to, but by myself I will never be able encapsulate a collective experience, because I don't have it. Within this field of study, there is no way that I was gonna do it by myself.

"Seeds in the Soil" by Yusuf Arslan

Making this zine, did you discover anything about yourself as an individual, as an artist, as a member of this wider diasporic community and the themes within Hinterland?

First of all, I realised how collective identity work is also in personal work. It was more so looking into what did I expect from this? From going in, and then what did I expect to come out of it? I thought it was going be a sort of like a coming home feeling. But by no means did I feel like I came home, and that I have it all now. It just made me keen to create more.

"Alma Kanaken" by Deniz-Can Sayim

Speaking with contributors and revisiting visual archives, I became more aware how layered that my own sense of belonging really was. That I have a place in all of this. I have a place in all of this.

It sounds as if the working on this project was like a portal for you, bringing you to the beginning of greater journey.

A hundred percent. What sparked the idea of Hinterland initially was the gendered experience of being othered, and then I moved towards a different direction.

What I've come to realise is society sees certain women, whether it may be Muslim women or Kurdish women, Turkish women, Arab women, brown women, black women, more as lacking agency, submissive, passive in society. Nobody knows what's happening behind closed doors.

What I then realised, on the other hand, is that the men of my culture, the men of my family, how are they being looked at? How are they being treated?

It sounds weird to say, but I come from so much privilege, and especially in the context of growing up in Germany, I was able to code switch.

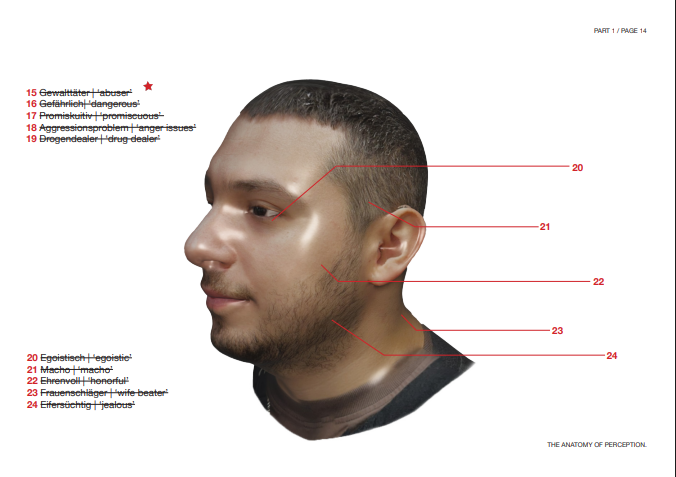

Anatomy of Perception

I was able to - I don't want to say integrate, I want to say assimilate - in a way that was digestible, maybe, for the people around me. And then I realised it may be a lot more difficult for men to do so, because men are not being seen as passive. I mean, my brother grew a beard when he was like eleven years old. He's being read just walking down the streets.

I wanted to ask you about the cover image of Hinterland in relation to what you think of the part that art has to play in the stories of diasporic peoples going forward?

So, the cover I left for last. I struggled with it. I didn't know what would encapsulate everything. Again, I wasn't doing that well mentally, at the time. The act of tearing and ripping and sewing back together was therapeutic and calming. I loved using my hands. There was something so beautiful about seeing the fragments being stitched together.

And I think art has the power to shift the lens. To move us from being like, you know, subjects of representations, to agents of it. The arts can document and confront and heal, all at once. It is a tool for visibility and transformation, and it can keep these stories from being flattened into stereotypes, andequally it can do the opposite.

Through Papercuts we see many characters embodied and their stories are revealed to us through visual cues. What it was like “wear” the faces of others?

It felt confronting and liberating at once, and I quickly realised that I was emotionally charged when I did this.

I was in my tiny flat share room with a camera cramped into one corner. I had a lot of props and different things, and I realized, by the end of it, I was so tired. I thought to myself, what a privilege it is. Like, I can take these off. I can put these on, and I can take these off, right?

That’s why I found it important to stay critical with myself. Because, again, you can be part of a community but perpetuate the same issues. Yes, I am here and I am part of it, but there might be a collective experience that I don’t knowabout.

And I am in a situation where it’s like a mask to me. It made me realise about how identity is constantly performed and interpreted often without any consent.

Papercuts

There are real stories and experiences but they’re not mine. It's fiction and nonfiction. These are real life people. In my case, it was something I slid into. I could visualise how stories intersect and even when paths differ.

And I feel like that fragmentation… I didn't know whether the pictures themselves were going to speak enough for themselves, so I ripped some and then glued them back on together, I stitched some stuff, I added these aspects and just couldn't stop. Eventually, I was like, okay, I need to leave it because, I'm gonna burn this whole house down.

Was there anyone else, anything else, that inspired you?

I remember coming across an annotated illustration in a biology book. Something about that resonated so much with me that it inspired me to work on something that designated meaning or better assigned it based on the visual markers, not constrained to but more often exhibited within individuals of the researched diaspora.

I have to say, I should have dedicated the zine to my brother. It was inspired by a lot of experiences that he's unfortunately had in his life. I didn't know what to do with them. He doesn't know what to do with them. And I was like, as his bigger sister, I was like, oh my god… I think that's what inspired me, really.

Well, we can dedicate this interview to him. What's his name? Let's shout him out.

Kubilay, we call him Kubi sometimes Momos. Don’t ask why.

You can follow Afra on Instagram @afr_a

Interview by Angelo Mikhaeil