In conversation with Dr Georgina Portelli, Vice Chair at MICAS (Malta International Contemporary Arts Space)

“The museum is not about buildings, is it? Museums are about reaching your audiences.”

- Dr Georgina Portelli

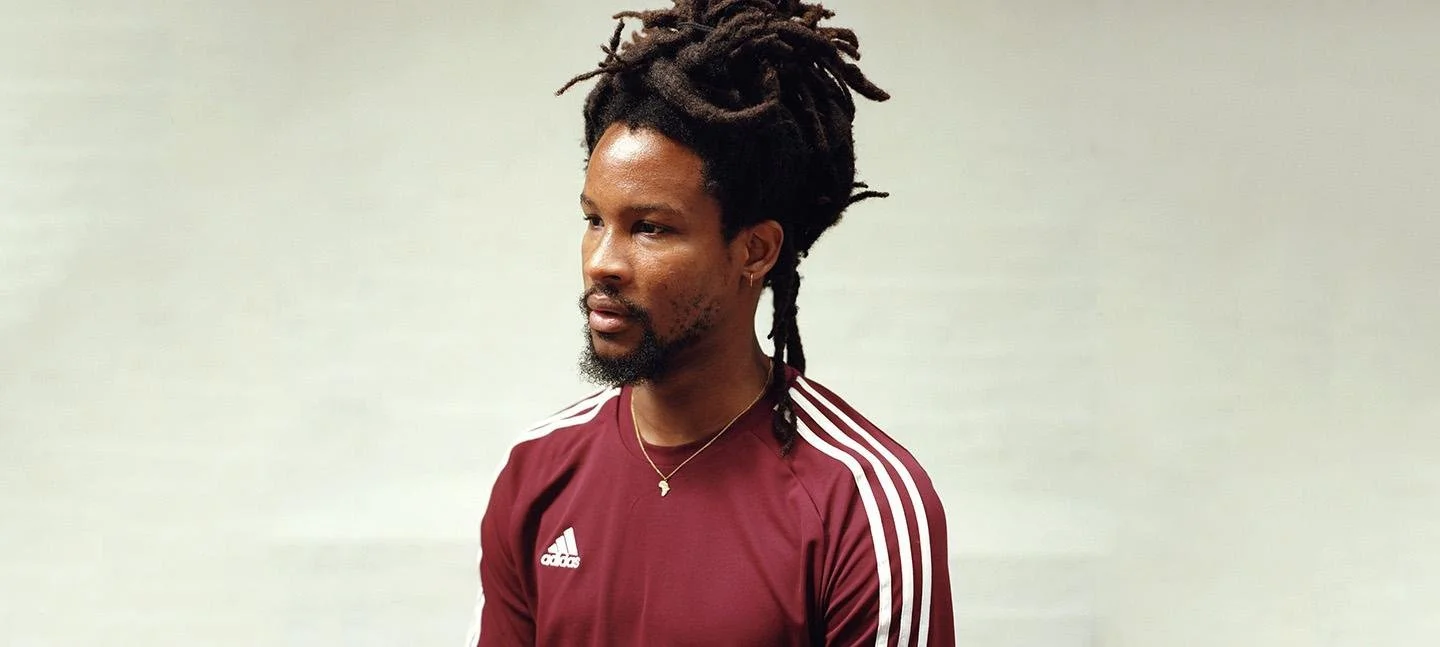

Dr Georgina Portelli. Vice Chair, MICAS (Malta International Contemporary Arts Space). Image credit Lourdes Photography

A little while back, we published our Malta guide to the island’s best cultural sights and activities, as well where to eat, sleep and relax. If you read our tips, you will know there is a lot more to ‘The Rock’ than beaches alone, and its cultural scene far more varied than its rich and complex history. Heritage and sunbathing as stunning and unique as they evidently are, our guide was spurred on specifically by recent world class moves within the cultural landscape – namely, the advent of Malta International Contemporary Arts Space(MICAS). A major national institution for contemporary art –built into the historic 17th Century of the Floriana bastions, just on the edge of the country’s capital Valletta – MICAS has been much anticipated for many decades, and its arrival did not disappoint. Already, its international programme has presented names such as Joana Vasconcelos, Ugo Rondinone, Conrad Shawcross and Milton Avery, alongside a globally exhibiting selection of Maltese artists.

It was a privilege to dig deeper into the past, present and future of this wonderful institution, with MICAS’s Vice Chair Dr Georgina Portelli. Someone who has lobbied hard for a contemporary art museum for over 30 years and a co-author of the country’s last cultural policy – as well as someone who also has a base in neuroscience – Portelli’s understanding of the cultural ecology is exceptional, and we were thrilled that she took the time to share such insight with us.

The arrival of MICAS as a permanent contemporary art museum in Malta has been very much anticipated since the idea was made known. What were the challenges in the initial stages?

Maltese artists and cultural champions have been lobbying for a contemporary art institution for over 50 years. So, we should give credit to the to those people, who certainly drove hard to convince society and the politicians. It's not that the cultural production or the creativity or the talent wasn’t there. All these artists were producing contemporary art. They went about their business. They didn't wait for the museum to open. And of course, in Malta we have three World Heritage sites. It's not as if we are not culturally connected, but what we lacked was an institution that was visible in terms of contemporary art. So we needed to fill that gap – that was very clear.

The first time the authorities recognised this was in the first cultural policy in 2011, and this was further consolidated in 2013 when the government program identified the setting up of an institution and the construction of a contemporary art museum. MICAS was never envisaged as a set of galleries or just galleries. It was envisaged as a platform that would certainly be a museum that hosted international art, that could cater for these exhibitions in the proper way, but also as a platform for education, for communities.

So the concept is much wider than simply a gallery space, but of course the first hurdle was finding the right site. Malta is a bit like Jerusalem, I would say, there are so many historical sites. It's a tiny island. We also needed to factor in what was more sustainable. So, using one of these heritage sites was a better option in terms of sustainability. It was not about spectacle in that sense. It was more about utilising a site that had the right spaces to offer so that the curatorial vision and the national vision could be realised. With regards to funding, the initial funding was spared by a European Regional Development Fund, around nine million that was devoted to the building of the galleries. However, the total investment from national funds, together with this European funding, came close to about 30 million so that was ensured once the politicians were convinced and the project went ahead.

There was a committee looking after national cultural projects that was headed by Phyllis Muscat – I was also part of that committee – which later then translated into the MICAS agency board, which we still have today. And that's more or less how the timing and the site and the funding came together. We managed to deliver the museum in 2024, we opened in October. So, we're fairly young. I mean, you can consider us a startup, however, with the ambition to move forward.

MICAS (Malta International Contemporary Arts Space). Image credit Kevin Kiomall

And before the permanent space was realised, you were doing offsite projects?

Yes, the museum is not about buildings, is it? Museums are about reaching your audiences. Education is certainly about increasing cultural capital too, and ensuring that the public encounters contemporary art. So our intention was always to launch a program. It was a program that looked at at least one international exhibition a year. We started in 2018 by inviting artist Swiss artist Ugo Rondinone and we commissioned the sculpture The Radiant. It is now on the forecourt of the museum. We are not exactly a collecting museum, but what has always been part of our vision is that if we do acquisitions, the acquisitions have to be democratically accessible. So, our vision was that the art we acquire, the public can encounter on the grounds of MICAS. The galleries would offer the rotating exhibitions, but the other spaces would be where the general public can encounter the acquisitions and counter contemporary art.

Also on the forecourt is another sculpture by British artist Conrad Shawcross, The Dappled Light of the Sun, which is also a large steel sculpture. Of course, we don't want to fill everywhere with sculpture. This is about encountering art and making, but with a vision.

Can we speak a little about the space itself – the historic site?

The space is a is a historic landscape. It is essentially 17th and 18th Century military architecture built by the Knights of St John, the Knights Hospitaller, who, when they built Valletta after a devastating siege in 1565 realised that their city walls could only face a seaward attack, but a land attack would leave them vulnerable. So, they built these series of walls, which are known as the Floriana Lines. And this is where MICAS is nestled. So the MICAS galleries are essentially situated in a ditch, a ditch that is known as the ritirata, which literally means a retreat. This ditch was spanned by a large arch where, essentially, if your enemy was on the adjacent walls, you would blow up this arch and retreat back to Valletta and isolate your enemy on the adjacent walls. So the Floriana Lines themselves are heavily layered with history.

The other thing that MICAS does as a museum, is that it takes heritage, but not as a monument. So, it acknowledges the layers of history. But these layers are not obscured or sentimentalised. You see them as you walk in the galleries, as you descend, as you are seeing the contemporary art that is displayed there. You discover these facets. It's all about movement, really. So that is where the concept is slightly different. I would say MICAS is more of a hybrid museum too. It is a museum that is not quite a kunsthalle, because we still acquire some art. However, we don't have a collecting indoor policy, in that sense, but we go for rotating exhibitions.

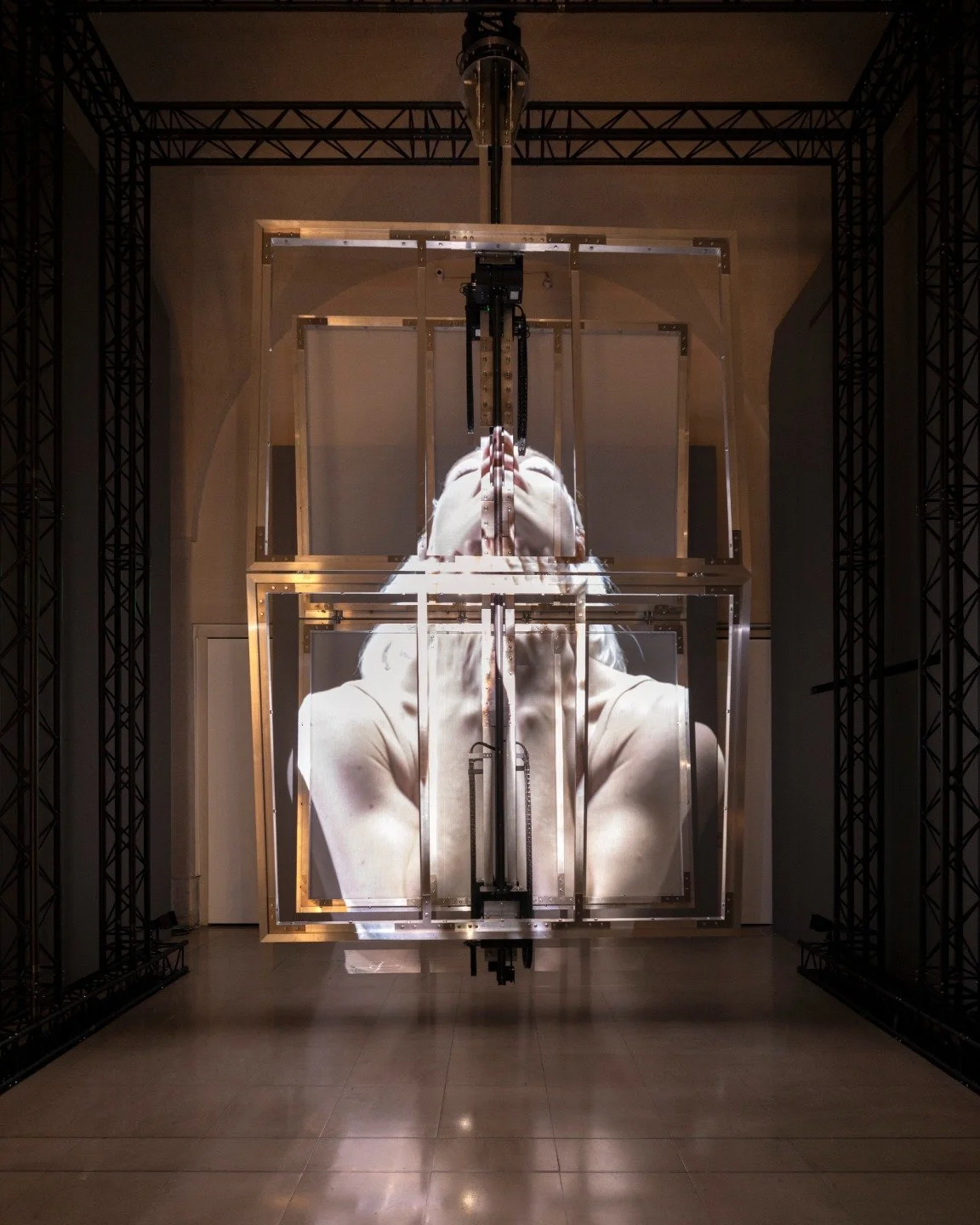

Installation shots of the Joana Vasconcelos exhibition. Image credit Roberto Goodman

What is so special about the specific design, which was created by Ipostudio?

We partnered with the restoration directorate – that is the body that is responsible for restoration and conservation in Malta, because the site is a historical site. It is something that had to be approached with sensitivity. And when we published the call out it was given to the best designs that suited our remit. Ipostudio is a Florentine based firm. They work a lot in with public buildings, and their idea was to secure the thelegibility of the site, that is, you could see the site as it was. Their design is essentially made up of a cartesian grid that is like a steel cover, of course with glass because we wanted the light that allows you to display contemporary art against this backdrop of spectacular sheer walls. And of course, that spectacular arch itself that leads you on to the harbour.

And why did we go for this? Because it was so tied up with the concept behind MICAS, that Malta is open as always – as it has always been throughout the centuries, the harboursbeing where the knowledge exchange happened. The arch itself is a window onto the harbour and the horizon. This concept was very much the core of the structure itself. So, we have the cover over the ritirata, and you can read instantly what the ritirata was, a series of terraces, essentially, and the ditch, however, you can now move through it.

The heritage is part of this curatorial vision. So of course you have to take into account that you are in a historic site, but this is quite harmonious. It is also a challenge, but I think these exhibitions we've had on site give an indication of how dynamic the galleries are, because it's not a white box, is it? It's not a white cube. So it offers challenges to the curators and to artists, but then again, it is highly dynamic. You it can change in so many ways, and that's what makes it interesting. Look at the exhibitions by Joana Vasconcelos, who made such good use of the of the height of the site. I mean, the lower gallery has a height of 19 metres, actually. So, you know, exhibiting The Tree of Life there actually, more height needed to be added to that, as it’s fairy high, but it's a wonderful space in that sense that you can really interrogate the raw space as it was.

Except for one gallery, you can see all the galleries from when you enter. So there's nothing in between that stops you from seeing what's coming next. And of course, that's also quite challenging curatorially, but I think it's also quite exciting in that sense that you can try and formulate an exhibition plan. It has to be different. It cannot be like anywhere else, but the site itself offers these possibilities.

You mentioned Joana Vasconcelos – what was it that made you wish to launch the space with an exhibition of her work?

What Joanna Vasconcelos offered was spectacle, certainly, but also accessibility. We were quite sure that her work, because of its monumentality, would interrogate the space in a fantastic way. She's a highly creative artist. She's using monumentality but using the most feminine of crafts. There's the softness, there's the thousands of sequins, the amount of colour – I think she had all the right ingredients to showcase what MICAS could be about. It is about accessibility. It's about communities. It is about encountering spectacles butencountering international art as well from a Malta based perspective. But it's also showing that the galleries can host quite significant exhibitions, exhibitions that require volume. So, I think it was important in that sense, and that's why we approached Joana Vasconcelos. And I must say it was an extremely, extremely successful exhibition, bright, sunny, yes, fun, because the element the fun certainly was there. She also insisted that visitors could touch the exhibits which made the art so accessible. Of course, some people might have been horrified. But we must say, children loved it. Families loved it. The fact that she was using these craft crochet, knitting materials, craft materials. I mean, we could see intergenerationally families visiting grandmothers, their granddaughters. You know, all certainly very, very much enthusiastic about the work. And I think it we were right in in the choice, because we saw the right enthusiasm for the galleries and the work.

And more recently, you presented the exhibition The Space We Inhabit, a show of six important Maltese artists. Can you tell us about the exhibition, its significance for Maltese artists, and how it fits into MICAS’s broader vision?

The Space We Inhabit was actually the second time that we held a Maltese artist exhibition. The first was part of the MICAS vision to have a virtual platform – partly as a curatorial tool, but also as a way of extending the museum and giving the museum presence in in the virtual world. Also, it's another way of documenting exhibitions that happened. When Covid happened and set us back in trying to deliver the museums, part of what we did at that point was accelerate this, and we decided to host an exhibition of Maltese artists within the virtual galleries.

The Space We Inhabit was an important milestone, though, because of course we are about the international art, and I include Maltese artists in this. I mean, I really do not like the dichotomy of what is local, what is international? Our artists are international. They exhibit abroad. There's always been this exchange but giving a multi focus was important. Edith Devaney, our Artistic Director, set about looking at the ecology itself, you know, looking at the canon, and she came up with a very interesting exhibition, which our artists were also very intrigued by. They had to work with a curator. For a very long time, all these artists were quite used to being their own curator. You know, they're artist-curators. The majority came from a group that was very active in the 90s, who were also quite vocal in their calls for a contemporary art museum, but they also had quite an established practice. We had the very strong painters – Vince Briffa, Anton Grech, Joyce Camilleri, Austin Camilleri. We also had the conceptual artists. Austin Camilleri is sort of multi-faceted there, showing a very intriguing piece of work, as did Pierre Portelli, and of course the oldest artist in the group, Caesar Attard, whose work was very conceptual, very interesting, very cerebral. We were very pleased with the reception, and it also gives the local artistic community the sense of what MICAS intends to do in terms of ensuring that Maltese artists have this platform.

Installation shots from The Space We Inhabit. Image credit Roberto Goodman

Looking at the current show of work by Milton Avery, this is very different – can you speak about the balance of different types of shows?

Yes, obviously there's that balance. The Milton Avery show is something different, it’s a more academic exhibition. We want a mix of exhibitions. Not every exhibition will be the same, but it also shows the MICAS vision in terms of what it intends to do. And I think the international reception for this curatorial vision is quite enthusiastic. It's well received. So,we are happy to go forward in that direction. It cannot be just one or the other. As I said, this is an international platform. Anyone who sits on the platform is considered international in that sense.

Where do you feel MICAS sits within the wider ecology, or artistic scene in Malta right now?

I have to be honest; the scene has been there for quite a while. It is not as if MICAS is generating this. I mean, we are part of an established ecology. We are the newcomers in the ecology. Yes, I think the advent of MICAS will drive, as we hope, further development of the scene. The ecology is there. There are some very well-established galleries as well. Of course, this might help also establish the proper gallery scene which is still absent. Most of our artists are not represented by galleries.

And of course, we are not a commercial gallery, we're a national institution. But if this engenders development – of course it is what we hope to see. The scene itself has always been fairly strong. We have a very specific remit. But of course, this is where boundaries are pushed as well. And that's the scene we want to encourage, but it's not our role to regulate. It's not our role at all. It's a very inventive and creative scene, which had to be so for a number of years, because there was nothing that that supported it – institutionally, that is. It’s good to see it progress in this way, and I hope MICAS can support this and, of course, see the outcomes too.

Installation images, Milton Avery exhibition. Image credit Sean Mallia.

You touched on the importance of education – can you go into detail about some elements of the education programme?

Yes, we have a strong educational program, and, of course, a strong education agreement. I mean not just for schools; this is also about adult education and conferences and bringing the discussion about contemporary art to the fore.

From an educational perspective, one other thing that we take quite seriously is the landscape policy at MICAS, which is essentially about populating the site with indigenous plants in Malta, so it's more like a collection. It’s also one way in which the public can come into context with indigenous plants. This is the policy for the for the sculpture garden as well, and any other space that needs planting. So, this is not just as a showcase in that sense, but because MICAS itself, although it's within the highly industrialized harbour area, we are also adjacent to what we call a Nature 2000 site, which are designated by the EU as important ecologically. So there's a pinetum, which is a large area filled with pine trees that is important for migrating birds. Also, we are within an urban landscape, Floriana, that has a large number of gardens itself. So this was very much part of our educational policy. And also the museum policy itself, to link up these green corridors, which is an extremely important aspect of the museum concept itself. And I must also say that MICAS has free entry in the weekends. And we also have open days in which, from an educational perspective, we provide a lot of activities for families, to, you know, to enjoy the museum and the museum experience.

And is there anything that you're really excited about coming up?

Yes, I'm certainly excited about the next exhibition by Reggie Burrows Hodges, an American artist who actually came to Malta for a year and produced an interesting body of work. We are very excited – it is quite an extensive exhibition with large pieces, which I really want to see hanging at MICAS, as another iteration of what the galleries can do.

I'm also excited about the next phase of the development, which is the development of the sculpture garden, which I'm stewarding at the moment. We have a lot of open spaces at MICAS. We also have a counterguard that sits above the galleries themselves, which is a fairly large area. It's a soil filled bastion, and we want to create this garden. So hopefully this kicks off towards the end of the year. And we will have certainly one Cristina Iglesias piece that we had commissioned, which is currently in a in a public garden in Valletta. This will be the piece that will remain in place, while we will also have either temporary commissions, or rotating work. And it would be the other phase of place making. We want to see these areas that have been out of bounds to the public for over 200 years. So, in terms of democratisation, you know, this is something we are looking forward to, particularly the democratization also of the harbour scapes, as I said, which have been out of sight for so long.

We can’t wait to revisit soon. To finish off our conversation, please could you finish the sentence, “MICAS is a place for…”

Well, MICAS is a place for communities, mostly. It's a place for creatives. It's a place for people who want to encounter contemporary art. It's also a place for anyone who wants to, you know, just have a walk about.

Colour Form and Composition: Milton Avery and His Enduring Influence on Contemporary Painting runs until 4 April 2026.

Beyond the Bastions runs until June 2026.

Reggie Burrows Hodges: Mela opens to the public 8 May 2026.

For more information, visit micas.art; Instagram: @micasmalta