Seeds of Hate and Hope at the Sainsbury Centre, Norwich review

As you ascend the winding staircase into the upper galleries of the impressive, Norman Foster-designed Sainsbury Centre, a red light begins to flicker. It belongs to Mona Hatoum’s iconic Hot Spot: a globe constructed from steel rods, on which the outlines of every continent gleam in an ominous neon red, representing the perma-status of unrest in which we find ourselves. Created in 2006, Hot Spot holds the same potency nearly twenty years later, tragically enriched by new and ongoing conflicts and countless lives lost. In fact, according to the wall text, “the occurrence of global conflicts has almost doubled in the last five years.” As that alarming statistic reveals, the world is becoming a more unstable and dangerous place. The question that therefore arises is: what role does art play in all this?

Mona Hatoum, Hot Spot, 2006. Stainless steel, neon tube. Courtesy of the David and Indrė Roberts Collection. © Mona Hatoum. All rights reserved, DACS 2025. Image courtesy of White Cube. Photo: Stephen White

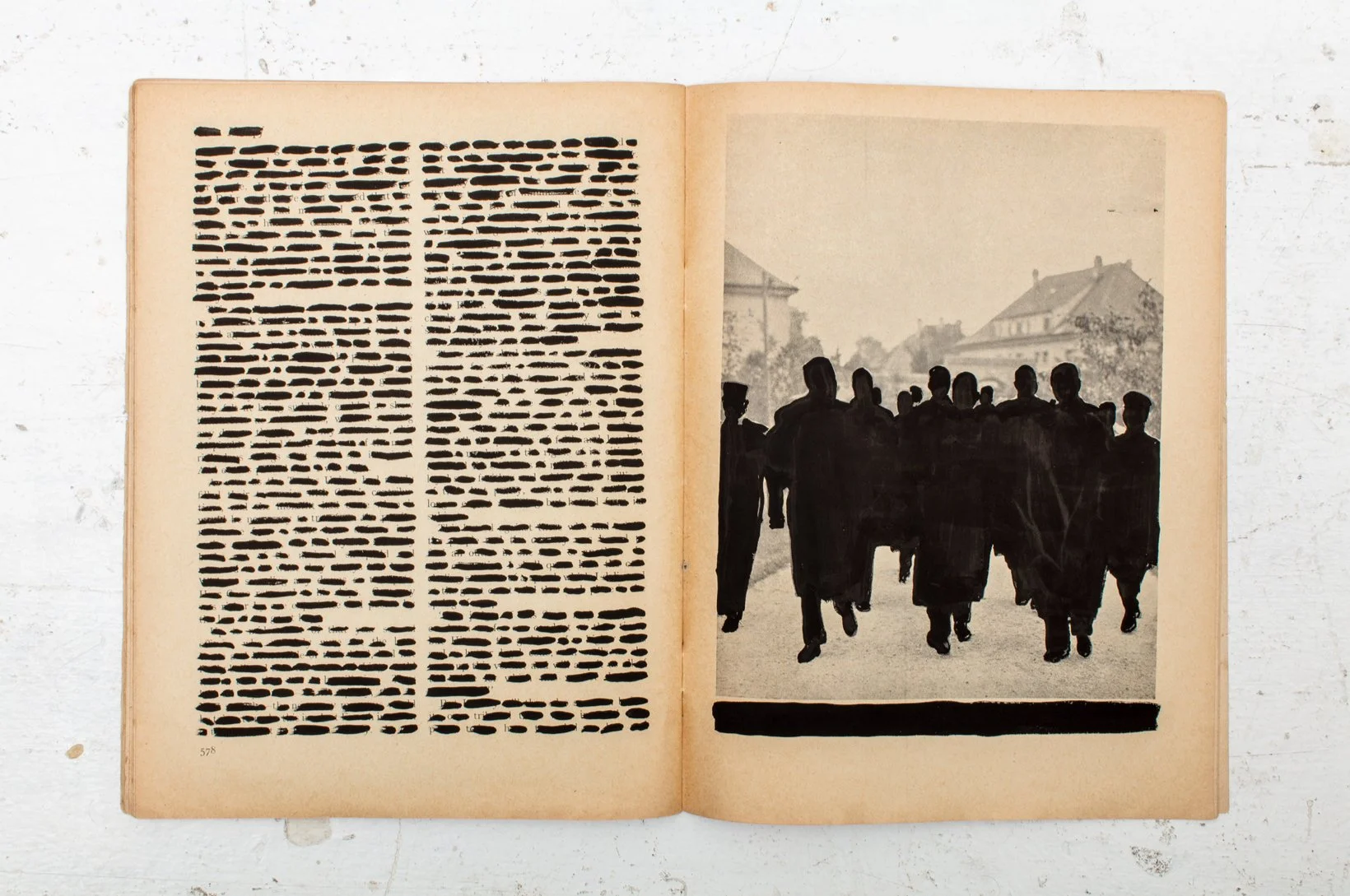

During our guided tour, co-curator Tafadzwa Makwabarara emphasises that the artworks chosen for Seeds of Hate and Hope steer away from shock value and instead offer an array of creative reflections and responses to global atrocities. No images of violence are on display here, and at a quick glance, a visitor might not even be able to guess the subject matter of the exhibition. Instead, the projects on display require, and definitely reward, close looking. A particularly thought-provoking work is Gideon Rubin’s Black Book (2017), which redacts every page of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf. With a thick black marker, the artist has painstakingly crossed out and shaded in every word and picture in the book, leaving just the outlines of paragraphs and illustrations visible.

Gideon Rubin, Black Book, Adolf Hitler covered over, gouache on printed paper (p.16), 2017

Rubin’s work prompts us to reflect on how ideologies are transmitted, and the ways in which words infiltrate the world beyond the page. Considering this from an almost inverse position, Alfredo Jaar’s series Untitled, Newsweek is a visceral demonstration of media indifference during the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. It becomes clear from these examples alone that art has a unique ability to critique dangerous narratives propagated in text and the media. This is key to the exhibition’s aim of uncovering how seeds of both hate and hope may be planted during conflicts, and it justifies the curatorial decision to focus on events of the previous century rather than contemporary ones.

Many of the exhibited artworks demonstrate how the impacts of mass atrocities extend far beyond the events themselves, and how reparative and restorative work can take decades. In William Kentridge’s animated film Ubu tells the truth, the artist confronts the legacies of Apartheid by blending fact and fiction to absurd effect. He combines archival footage of protests and police brutality in South Africa with cartoon drawings, photographic material, and animations relating to Alfred Jarry’s seminal play Ubu Roi. The result is disorientating and topical in the supposed “post-truth” era we find ourselves in. The idea of an objective truth in the context of conflict is particularly thorny, and yet often plays a significant role in individuals’ and nations’ identity-building. British artist David Cotterrell explores this phenomenon in his double-screen video work Mirror IV: Legacy, in which six Rwandan actors of the post-genocide generation read the same monologue aloud. However, half have been told that their character’s father was a victim, and the other half that their character’s father was a perpetrator. As viewers, we become intensely attuned to any movement in the actors’ faces, attempting to read inherited guilt or victimhood into every twitch. The result is decidedly uneasy and forces us to consider the mechanisms through which generational trauma persists.

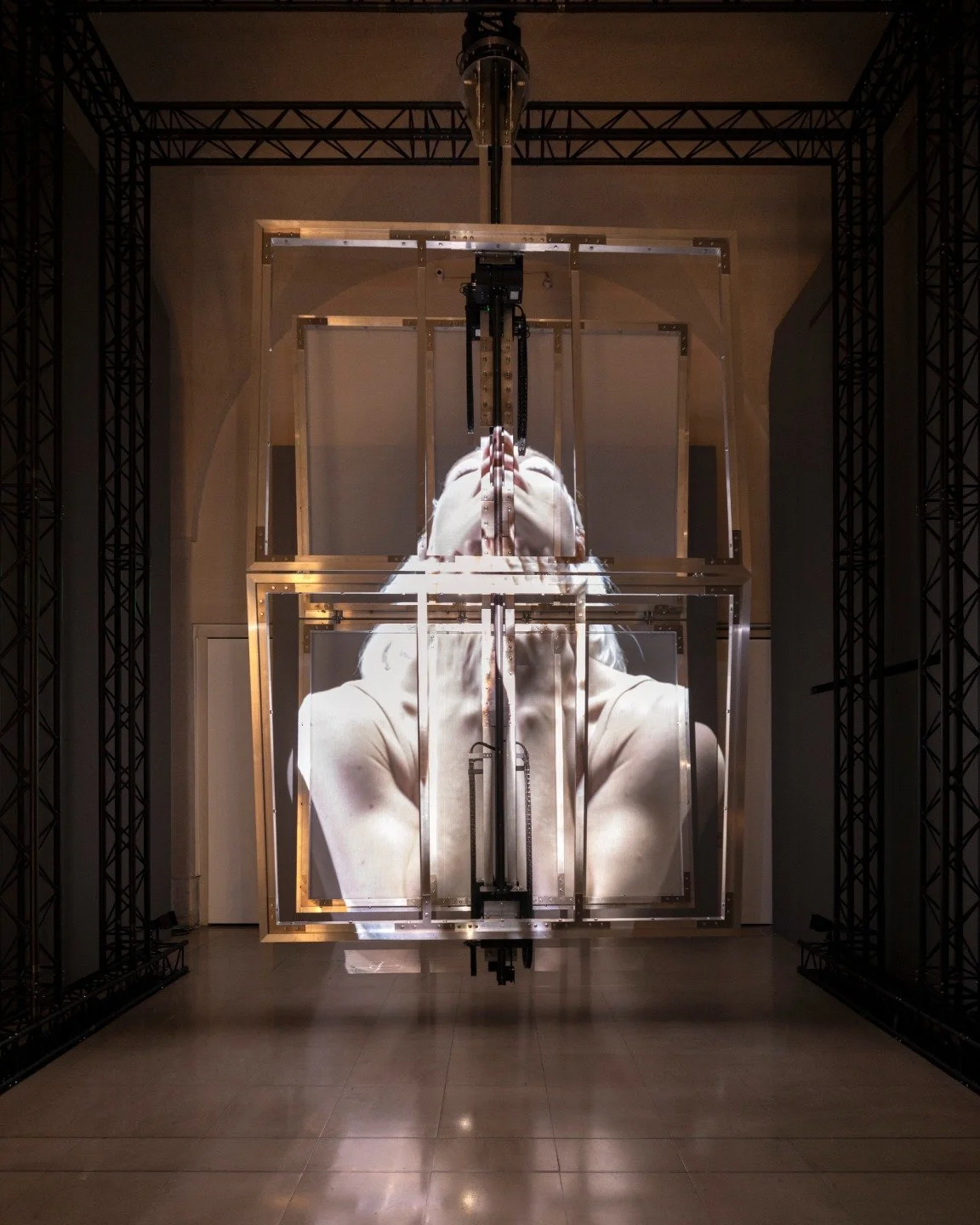

David Cotterrell, Mirror IV: Legacy, 2015, video. © David Cotterrell, 2018. Image courtesy of the artist.

This exhibition forms part of a broader programme at The Sainsbury Centre which asks vital, fundamental questions. Seeds of Hate and Hope was one of several shows curated in light of the question: Can we stop killing each other? While global events continue to put forward a negative answer to that question, this exhibition successfully proposes art as a crucial tool for understanding history and restoring a sense of shared humanity in the face of such horrors.

Date: 28 November - 17 May 2026. Location: Sainsbury Centre, University of East Anglia, Norwich, Norfolk, NR4 7TJ. Price: Pay If and What You Can. sainsburycentre.ac.uk

Review by Sofia Carreira-Wham

This week in London (16–22 February 2026), Ryoji Ikeda takes over the Barbican Centre with performances exploring sound and light, while FAC51 The Haçienda comes to Drumsheds for a full day of classic house and techno. New exhibitions open across the city, including Chiharu Shiota’s thread installations at the Hayward Gallery and Christine Kozlov at Raven Row…

With Six Nations 2026 starting on 5 February, London is packed with pubs, bars and restaurants showing every match…

Somerset House Studios returns with Assembly 2026, a three-day festival of experimental sound, music, and performance from 26–28 March. The event features UK premieres, live experiments, and immersive installations by artists including Jasleen Kaur, Laurel Halo & Hanne Lippard, felicita, Onyeka Igwe, Ellen Arkbro, Hannan Jones & Samir Kennedy, and DeForrest Brown, Jr…

This week brings fresh details from some of the UK’s most anticipated exhibitions and events, from Tate Modern’s Ana Mendieta retrospective and David Hockney’s presentation at Serpentine North to the British Museum’s acquisition of a £35 million Tudor pendant…

This week in London (2–8 Feb 2026) enjoy Classical Mixtape at Southbank, Arcadia at The Old Vic, Kew’s Orchid Festival, Dracula at Noël Coward Theatre, free Art After Dark, Chadwick Boseman’s Deep Azure, the Taylor Wessing Portrait Prize, and Michael Clark’s Satie Studs at the Serpentine…

SACHI has launched a limited-edition Matcha Tasting Menu in partnership with ceremonial-grade matcha specialists SAYURI, and we went along to try it…

Croydon is set to make history as the first London borough to host The National Gallery: Art On Your Doorstep, a major free outdoor exhibition bringing life-sized reproductions of world-famous paintings into public spaces…

February in London sets the tone for the year ahead, with landmark exhibitions, major theatre openings, late-night club culture and seasonal festivals taking over the city. From Kew’s 30th Orchid Festival to Tracey Emin at Tate Modern and rooftop walks at Alexandra Palace, here’s what not to miss in February 2026…

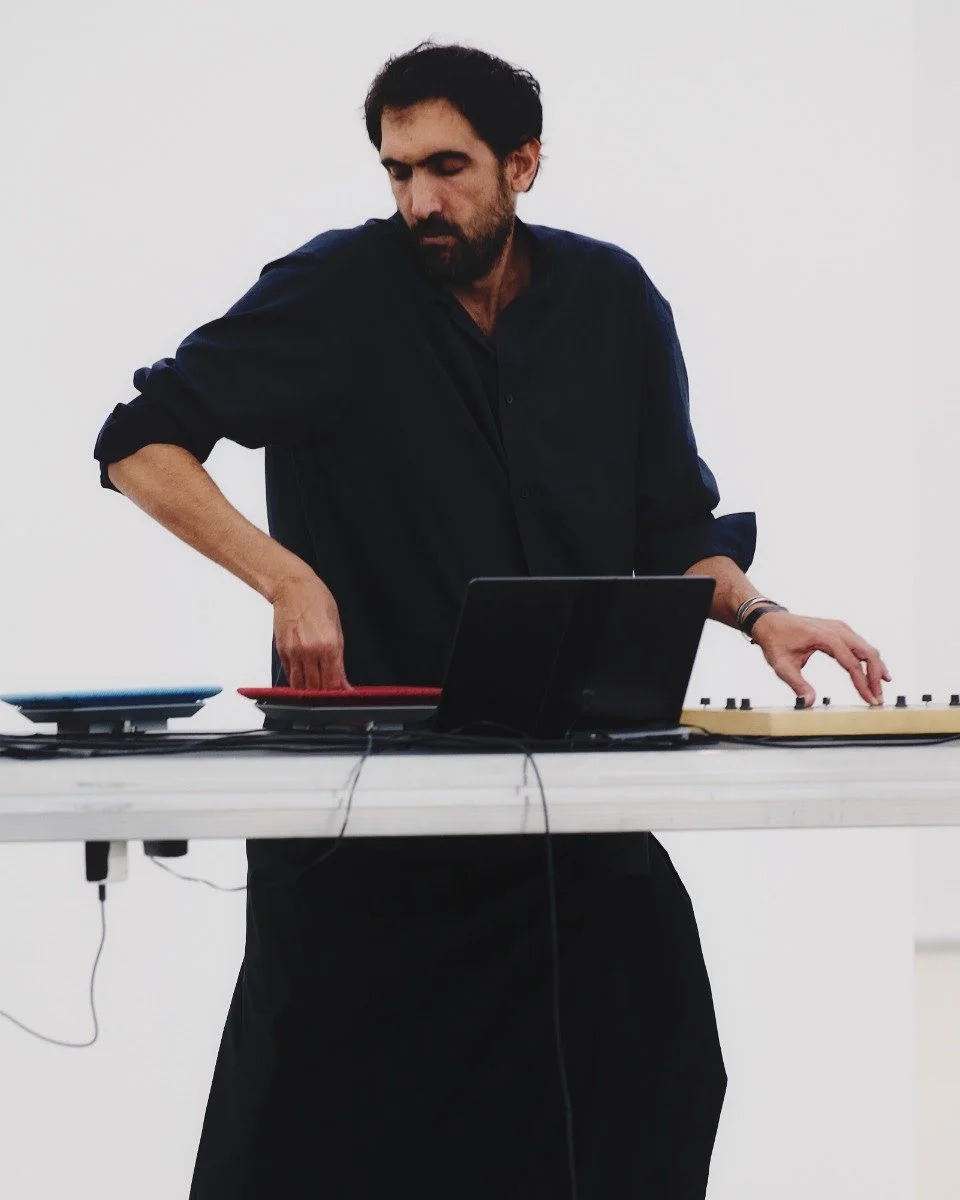

Tate Modern has announced that Tarek Atoui will create the next Hyundai Commission for the Turbine Hall. The artist and composer is known for works that explore sound as a physical and spatial experience…

Kicking off the London art calendar, LAF’s 38th edition at Islington showcased a mix of experimental newcomers and established favourites. Here are ten standout artists from London Art Fair 2026…

Discover a guide to some of the artist talks, as well as curator- and architecture-led discussions, to be on your radar in London in early 2026…

This week in London, not-to-miss events include the T.S. Eliot Prize Shortlist Readings, the final performances of David Eldridge’s End, the return of Condo London, new exhibitions, classical concerts, a film release, creative workshops, wellness sessions, and a standout food opening in Covent Garden with Dim Sum Library…

Plant-based cooking gets the Le Cordon Bleu treatment in a new series of London short courses…

January is your final opportunity to catch some of London’s most exciting and talked-about exhibitions of 2025. Spanning fashion, photography, contemporary sculpture and multimedia, a diverse range of shows are drawing to a close across the city…

As the new year begins, London’s cultural calendar quickly gathers momentum, offering a packed programme of exhibitions, festivals, performances and seasonal experiences throughout January. Here is our guide to things you can do in London in January 2026…

Condo London returns in January 2026 as a city‑wide, collaborative art programme unfolding across 50 galleries in 23 venues throughout the capital, from West London and Soho to South and East London. This initiative rethinks how contemporary art is shown and shared, inviting London galleries to host international…

The Southbank Centre has announced Classical Mixtape: A Live Takeover, a one-night-only, multi-venue event taking place in February 2026, bringing together more than 200 musicians from six orchestras across its riverside site…

This week in London features late-night Christmas shopping on Columbia Road, festive wreath-making workshops, live Brazilian jazz, mince pie cruises, theatre performances, art exhibitions, a Christmas disco, and volunteering opportunities with The Salvation Army.

Discover London’s unmissable 2026 fashion exhibitions, from over 200 pieces of the late Queen’s wardrobe at The King’s Gallery to the V&A’s showcase of Elsa Schiaparelli’s avant-garde designs and artistic collaborations…

Marking her largest UK project to date, Sedira’s work will respond to the unique architectural and historical context of the iconic Duveen Galleries, offering audiences an experience that merges the political, poetic, and personal…

This week in London, enjoy festive events including Carols at the Royal Albert Hall, LSO concerts, designer charity pop-ups, late-night shopping, art exhibitions, film screenings, foodie experiences, last-chance shows, and volunteer opportunities across the city…

Explore Belgravia this Christmas with a festive pub crawl through London’s most charming historic pubs, from The Grenadier’s cosy mews hideaway to The Nags Head’s quirky classic tavern…

From the joys of Christmas at Kew to the lively Smithfield meat auction, and from major concerts and ballets to intimate workshops and family-friendly trails, the city offers an extraordinary mix of experiences. This guide brings together the very best of Christmas in London…

This guide highlights some of the must-see art exhibitions to visit over the festive period in London, including the days between Christmas and New Year’s. From major retrospectives of international masters such as Kerry James Marshall, Wayne Thiebaud, and Anna Ancher, to engaging contemporary works by Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, Jennie Baptiste, and Tanoa Sasraku…

London’s cultural scene, a gallery or museum membership is the perfect alternative to another pair of socks. From unlimited access to exhibitions and exclusive events to discounts in shops and cafés, these memberships offer experiences that can be enjoyed throughout the year, while also supporting the vital work of arts organisations…

Your guide to London’s can’t-miss events this week, 17–23 November 2025, from Cabaret Voltaire live at ICA to Ballet Shoes at the National Theatre and The Evolution of UK Jazz at the Barbican…

Charlotte Winifred Guérard is a London-based artist and recent graduate of the Royal Academy of Arts School, where she was recognised as a Paul Smith’s Foundation scholar for her artistic achievement. Her work has been exhibited at the Royal Academy, Coleman Project Space, Fitzrovia Gallery, Messums and Palmer Gallery, and she has completed prestigious residencies including…

This week in London, you can enjoy festive ice skating, Christmas lights, jazz and classical concerts, and a range of art exhibitions. Highlights include Skate at Somerset House, Christmas at Kew, the EFG Jazz Festival, and the Taylor Wessing Photo Portrait Prize 2025…

From the 6th to the 9th of November, the leading West African art fair Art X Lagos celebrates its 10th birthday at the Federal Palace on Victoria Island. Founded by Tokini Peterside-Schwebig in 2016, the fair has become an unmissable event in the global art calendar, attracting galleries from over 70 countries and participants from 170 countries since its launch…

If you’re after something bold, queer and completely uncategorisable this November, you need to know about KUNSTY, the Southbank Centre’s brand new four day performance series running from 5-8 November 2025…